Wednesday, April 17, 1929

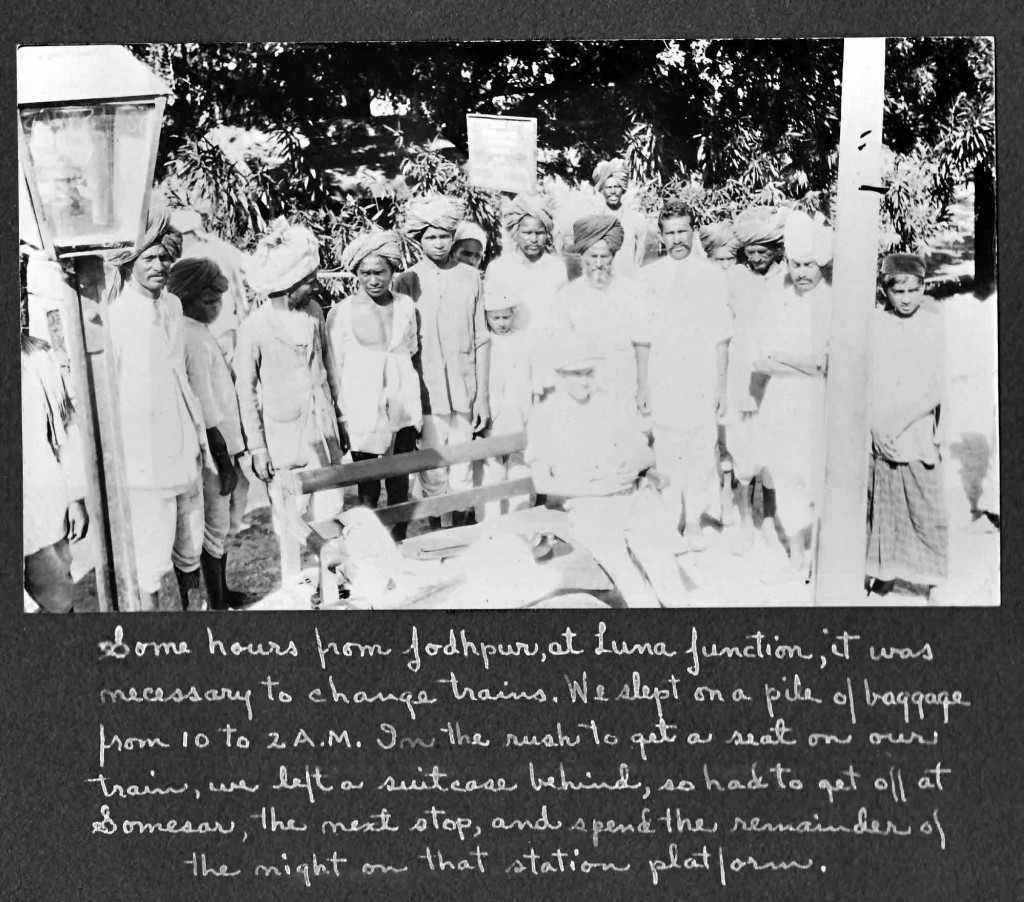

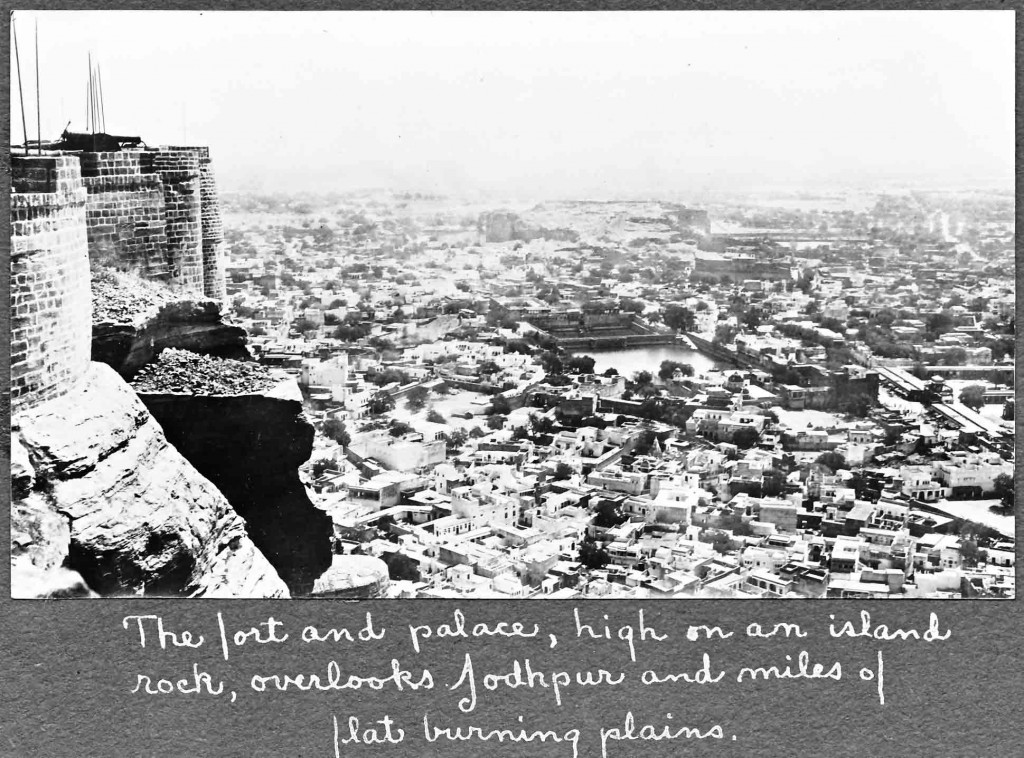

We arrived at Luni Junction about seven. Here the trains shift around, some going to Jodhpur and north toward Bickenar, others south to Marwar where a line goes to Ajmer, and another to Bombay. It did not take long to cover the twenty remaining miles north to Jodhpur, whose fort we could see many miles away on the top of a block of rock rising from the plain 400 feet. In the brush near the track we saw a doe, a couple of wild boars, lots of brilliantly colored birds, camels, and flocks of goats attended by shepherds. Hunting is said to be good near here. Small native huts, or groups of them, are all enclosed by a thick fence of bushes some five or seven feet in height.

Jodhpur is the capital of one of India’s 600-odd states and has over 71,000 inhabitants [846,408 in 2001]. Around the town is an ancient wall having seven gates. Within the walls is the fort, seeming to hang on the sheer edge of the perpendicular precipice, and within the fort are palaces.

We got a very nice room in the Dak Bungalow for 1r a day and two meals required, bringing the damages to three rupees or $1.11 per each per day. It has a large ceiling fan, a bathroom with a tin tub, and another small room, lots of windows and doors and lots of service which means lots of tips. Still, it is worth it—good food, a nice cool place to stay (as cool places go in this oven), good soft beds, and no bugs. A light breakfast of toast, eggs, and 4 cups of tea (having only had two in Lundi Junction), and a good bath. Then we set out to see things.

A Hindu temple sits are the end of the street, a block from our stone-club mansion. Of whitewashed stones and richly carved, it presents an interesting sight. Three graded stone terraces lead up to the part that is whitewashed. Most of the stone buildings that line the streets are of carved gray stone. And such carving, even on homes in poorer sections. A number are whitewashed and have colored paintings on the front, most of them of an elephant representing the goddess Ganesh, the son of Shiva, the great god, and is worshipped for good luck, success, and knowledge. On the main drag is another whitewashed temple in which we heard the tom-toms, etc. Two elephants, half-size, guard the door. The main street is a good bazaar. There you can see the weavers, sewers, tin workers, candy and sweets men, fruit and grain sellers, all busy at their business or sitting cross-legged in the midst of their wares on display in the small open shop. Sacred cows are in abundance, wandering all through the streets. Mort petted one and those who saw him beamed, one man even patting him on the back. Miserable beggars, terrible sights, are much in evidence. Many are but skin and bones, having feet or legs half-grown, twisted around in unbelievable shapes so they get around by walking on their hands, and numberless others, all miserable creatures. The small children go about naked or nearly so. The men wear all stages of dress and the women usually garb in gay colors, red, yellow, and green. The camera attracted a troop of kids who followed along like a Sunday school picnic and kindly posed each time we tried to take a picture.

Ascending a steep, twisting stone walk, we at last reached the first gate of the fort. Here one gets a magnificent view of Jodhpur, its temples, water tanks, and the flat busy plain stretching away to the horizon. We did not have the required pass for entrance, but the guard finally permitted us entrance. Up wound the steep stone road, turning and winding, through two more gates. Above, the walls and palaces towered, and on a tree growing from a crack in the perpendicular rock sat an eagle. At the fourth gate of the fort we were turned back by the guard because of no passes. There are seven gates in all. On the walls of this fourth gate are carved the hands of seventeen wives of the Maharajas who died through Sati. A man was pasting tin-foil over them, I suppose to preserve them.

Ascending a steep, twisting stone walk, we at last reached the first gate of the fort. Here one gets a magnificent view of Jodhpur, its temples, water tanks, and the flat busy plain stretching away to the horizon. We did not have the required pass for entrance, but the guard finally permitted us entrance. Up wound the steep stone road, turning and winding, through two more gates. Above, the walls and palaces towered, and on a tree growing from a crack in the perpendicular rock sat an eagle. At the fourth gate of the fort we were turned back by the guard because of no passes. There are seven gates in all. On the walls of this fourth gate are carved the hands of seventeen wives of the Maharajas who died through Sati. A man was pasting tin-foil over them, I suppose to preserve them.

On the return trip we descended a stony path followed by a dozen kids in many-colored turbans, Indian file. On the way down we came across a small shrine built at the base of the precipice. In it was a large god with the face of a monkey, three heads. It represents Hanuman, worshiped as the model of a faithful, devoted servant and is a reincarnation of Siva, rather of Rama, who represents Siva. Siva descended to earth in so many forms that it is confusing.

At the bottom we noticed some excitement at a tower high above us. The natives flocked about us and we gathered that a criminal was being executed and his body or he would be thrown from the battements to the rocks below. We stayed to see the sight. There were many natives near, and they gathered around and did their best to make us feel at home, giving us things to sit on in the shade of a tree, giving us water to drink, etc. After a while we learned that sacred buffaloes were to be sacrificed to the god Divi. This ceremony happens twice a year so we didn’t want to miss it. It is killed and the body tossed over. The poor natives rush up to where the animal lies and take the meat—so we gathered from the natives. After an hour and a half we gave it up and returned to the Dak Bungalow.

A policeman called at seven to get our names, etc. and sat about conversing for a while. He said the Maharaja’s secretary was at the Bungalow, so I grabbed a shirt and beat it out to get a pass to the fort. The secretary said he would send it to me this evening, which he did at dinner time, and with an invitation to tea and a ride the following afternoon. An Englishman, Mr. Dorton, who works for the Bombay branch of the General Electric Co. dropped in and forgot to leave till we chased him out to go to dinner. He had lots of interesting things to say as he had traveled India 8 years. Before long he had us all dead and buried for eating food from bazaars and drinking the water and a million other things. Has no use for America, as most Englishmen do, and seems to forget that while Americans live on bluff, Englishmen are twice as bad. Claims the Indians hoard their wealth, have most of the gold mined in Africa during the war hidden away underground here. The ornaments you see, even on the poorest, are of solid silver and 22-carat gold. He also informed me that the secretary of the Maharaja I was speaking to is his cousin, and a Raja in his own right. To be exact, he is Rao Saheb Raja Narpat Singhji, Comptroller of the Household and Private Secretary to Major His Highness Maharaja Sir Umed Singh Bahadur. The father of Narpat Singh was a famous Major General during the Great War. He ruled Jodhpur for years during the present Maharaja’s minority, the latter being 26 now.

and sat about conversing for a while. He said the Maharaja’s secretary was at the Bungalow, so I grabbed a shirt and beat it out to get a pass to the fort. The secretary said he would send it to me this evening, which he did at dinner time, and with an invitation to tea and a ride the following afternoon. An Englishman, Mr. Dorton, who works for the Bombay branch of the General Electric Co. dropped in and forgot to leave till we chased him out to go to dinner. He had lots of interesting things to say as he had traveled India 8 years. Before long he had us all dead and buried for eating food from bazaars and drinking the water and a million other things. Has no use for America, as most Englishmen do, and seems to forget that while Americans live on bluff, Englishmen are twice as bad. Claims the Indians hoard their wealth, have most of the gold mined in Africa during the war hidden away underground here. The ornaments you see, even on the poorest, are of solid silver and 22-carat gold. He also informed me that the secretary of the Maharaja I was speaking to is his cousin, and a Raja in his own right. To be exact, he is Rao Saheb Raja Narpat Singhji, Comptroller of the Household and Private Secretary to Major His Highness Maharaja Sir Umed Singh Bahadur. The father of Narpat Singh was a famous Major General during the Great War. He ruled Jodhpur for years during the present Maharaja’s minority, the latter being 26 now.