Sunday, May 19, 1929

Pancakes for breakfast again. Lussoo is getting the knack of making them now. This is the first day that there has not been a storm over the mountains or clouds over the city in the afternoon. Mort and Frank spent the morning on their newspaper stories while I sat up on our hanging garden and read “Magic Ladakh” by “Ganpat,” a British army officer. Mort discovered his razor missing, and while we were searching for it, it suddenly reappeared. The kid who carries the water and washes dishes had stolen it, but became frightened and brought it back. Lussoo was much disturbed and later Abdulla told us he had boxed the kid’s ears—which is evidently a terrible punishment over here. The kid looked sullen enough all morning.

Pancakes for breakfast again. Lussoo is getting the knack of making them now. This is the first day that there has not been a storm over the mountains or clouds over the city in the afternoon. Mort and Frank spent the morning on their newspaper stories while I sat up on our hanging garden and read “Magic Ladakh” by “Ganpat,” a British army officer. Mort discovered his razor missing, and while we were searching for it, it suddenly reappeared. The kid who carries the water and washes dishes had stolen it, but became frightened and brought it back. Lussoo was much disturbed and later Abdulla told us he had boxed the kid’s ears—which is evidently a terrible punishment over here. The kid looked sullen enough all morning.

After lunch, Frank, Abdulla, and I walked some three miles through the bazaars to a leather store. These bazaars are quite good, but few Europeans go through them, I guess. I didn’t see a one all the time we were in them. There one finds the usual cheap ornaments and also more expensive silver ones. Kashmirian women, as well as those of India, are extremely fond of ornaments. In Kashmir it is a common sight to see a woman having a large ring of silver through one lobe of her nose. The size of the ring varies, but many wear them some three inches in diameter, and they dangle down to their mouths. On their ears they wear from one ornament to perhaps a dozen on each ear. Some wear an ornament that is some three inches wide, of silver or of imitation silver, having perhaps a dozen small do-funnies dangling down from this larger piece of silver, and the total length 6 or 8 inches. Often these ear decorations hang down to the shoulders.

A white cloth is thrown over the head and hangs down over the shoulder and half-way down the back. Across the forehead a string of decorations is very often worn. But few of the women veil. As a rule, they are not so bad looking, sapping their beauty from the country in which they live. Sometimes the woman will have her black hair braided in a number of strings. This is more noticeable on young girls who do not wear anything on their head. Today I saw a young girl whose hair was braided as below. Her real hair extended to just below her shoulders, where hairs from a dyed yak’s tail were woven in and braided to complete the design. You know she doesn’t braid her hair every day, nor even every two weeks. The young gentleman above has not had a brick fall on his head. It is just a popular method of cutting a young boy’s hair. The head is shaved, leaving only the bang hanging down over the forehead.

A white cloth is thrown over the head and hangs down over the shoulder and half-way down the back. Across the forehead a string of decorations is very often worn. But few of the women veil. As a rule, they are not so bad looking, sapping their beauty from the country in which they live. Sometimes the woman will have her black hair braided in a number of strings. This is more noticeable on young girls who do not wear anything on their head. Today I saw a young girl whose hair was braided as below. Her real hair extended to just below her shoulders, where hairs from a dyed yak’s tail were woven in and braided to complete the design. You know she doesn’t braid her hair every day, nor even every two weeks. The young gentleman above has not had a brick fall on his head. It is just a popular method of cutting a young boy’s hair. The head is shaved, leaving only the bang hanging down over the forehead.

The ordinary woman or girl of over nine or ten wears a pair of tight-fitting pants beginning at her ankles and gathered in at the waist—I suppose. Then a shirt or blouse is usually worn, ending at the waist, and over all a slip-over dress of coarse material, open at the neck, having sleeves that are very full, and the whole hanging very loosely. The pants are usually red or brown, the shirt red, white, or brown, and the outer dress of heavier material brown as a rule. This outer dress may be a little more European than the other slip-over affair, but they all have long sleeves, are of a dark color, and reach at least to an inch or two of the ankles. Many women wear only the pants and a loose dress. If anything is worn on the feet, it is usually a kind of leather sandal, always much worn as are the rest of the clothes except in the case of a more well-to-do woman. Beads or ornaments are always worn about her neck. Often she bedecks her arms with many bracelets, her fingers with rings, her ankles with heavy silver bracelets, and her toes with toe-rings.

The ordinary woman or girl of over nine or ten wears a pair of tight-fitting pants beginning at her ankles and gathered in at the waist—I suppose. Then a shirt or blouse is usually worn, ending at the waist, and over all a slip-over dress of coarse material, open at the neck, having sleeves that are very full, and the whole hanging very loosely. The pants are usually red or brown, the shirt red, white, or brown, and the outer dress of heavier material brown as a rule. This outer dress may be a little more European than the other slip-over affair, but they all have long sleeves, are of a dark color, and reach at least to an inch or two of the ankles. Many women wear only the pants and a loose dress. If anything is worn on the feet, it is usually a kind of leather sandal, always much worn as are the rest of the clothes except in the case of a more well-to-do woman. Beads or ornaments are always worn about her neck. Often she bedecks her arms with many bracelets, her fingers with rings, her ankles with heavy silver bracelets, and her toes with toe-rings.

The younger women and girls are often attractive, but rarely does a woman retain her attractiveness after 30. She grows ugly, loses her teeth, loses the freshness of her skin, and does not carry herself gracefully. In comparison, the women of India are much more graceful and as a whole better-built. Also, the younger women and girls are better looking, sometimes pretty.

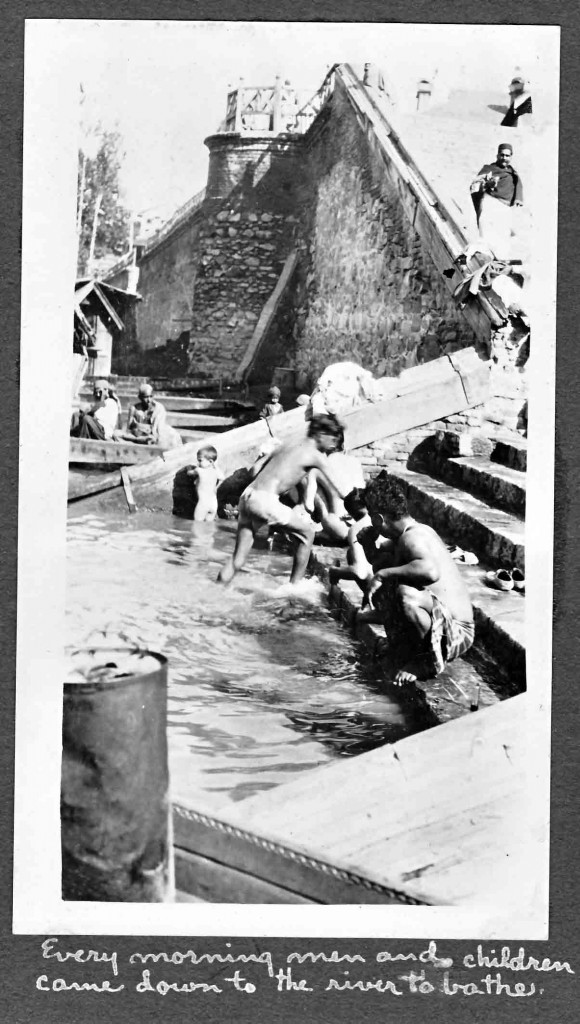

The men dress quite like those of India do. They sport a very loose pair of white pants, small at the ankles and wide at the top, being gathered in at the waist with a string. The crotch hangs down to just above the knees and make the appearance very sloppy, but I suppose it is cool. Under this is usually worn a loin cloth. In the morning when they bathe, if they do, they will disrobe to the loincloth and do their bathing that way. Xanadu is parked right in front of a bathing place here. Steps lead from the bazaar down the river bank to the water’s edge. Every morning many men come here to bathe in the muddy water. The children go in naked.

The men dress quite like those of India do. They sport a very loose pair of white pants, small at the ankles and wide at the top, being gathered in at the waist with a string. The crotch hangs down to just above the knees and make the appearance very sloppy, but I suppose it is cool. Under this is usually worn a loin cloth. In the morning when they bathe, if they do, they will disrobe to the loincloth and do their bathing that way. Xanadu is parked right in front of a bathing place here. Steps lead from the bazaar down the river bank to the water’s edge. Every morning many men come here to bathe in the muddy water. The children go in naked.

A shirt, mostly white with stripes, is worn and allowed to hang loosely over the pants, the shirt tails never being tucked in. Cuff-links are often worn and the sleeves are never rolled. Collar buttons are seldom worn and the men can never be accused of wearing a collar or tie. The turban is almost universally worn in Kashmir and that part of India in which we have so far traveled. There are a very few fezzes and those are not the good looking stiff ones of Egypt and Palestine, but squatty limp affairs. Skull caps are worn by the younger boys. In bazaars one sees many shops which sell only a small cap similar to a fez but not so tall, fitting closer to the head. These are all designed with gold and silver thread and of all colors. This colorful cap is worn under the turban often.

Holy men are not so much in evidence in Kashmir. First, the majority of people here are Mohammedans and secondly, it is too cool at nights for the nakedness of holy men.

The bazaars and houses of Srinagar are unique in that on the roofs grow grass and weeds. Evidently that thick layer of dirt helps keep out the rain—as long as there is not too much. As one looks down the street, these weeds give the impression of a hill behind the buildings. Most of the buildings are of sun-baked brick with much carved woodwork in evidence. This carving is usually found on the cornices and windows. The latter are of latticed wood, and have all been carved out.

Some buildings seem to lean toward a Swiss type of architecture or old English. This type is much more picturesque than other types. Along the river, especially near the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th bridges, are many old brick buildings, and most are curio shops or work shops making paper machie, wood-carvings, etc. I have visited a number of these, and you always enter by a small, unpretentious door in an alley-like street running up from the river. Climbing an old flight of steps in semi-darkness, you emerge from the dingy atmosphere into a room full of all sorts of Kashmir art-craft. On shelves and tables are all sorts of paper machie objects, and as a rule the work is very well done. In another part of the room one can see beautifully carved stands and tables for 15 rupees up, and elegantly carved cigarette boxes in the natural wood for 5 rupees up, the usual price being 6 to 10. Trays, vases, plates, and what-not, all finely carved of wood.

Some buildings seem to lean toward a Swiss type of architecture or old English. This type is much more picturesque than other types. Along the river, especially near the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th bridges, are many old brick buildings, and most are curio shops or work shops making paper machie, wood-carvings, etc. I have visited a number of these, and you always enter by a small, unpretentious door in an alley-like street running up from the river. Climbing an old flight of steps in semi-darkness, you emerge from the dingy atmosphere into a room full of all sorts of Kashmir art-craft. On shelves and tables are all sorts of paper machie objects, and as a rule the work is very well done. In another part of the room one can see beautifully carved stands and tables for 15 rupees up, and elegantly carved cigarette boxes in the natural wood for 5 rupees up, the usual price being 6 to 10. Trays, vases, plates, and what-not, all finely carved of wood.

Nearby may be a few odds and ends—old Hindu gods, old brass coffee pots and plates, a few dishes from Ladakh or Tibet, etc. In another corner are many shelves loaded with beautiful silk embroideries and all other kinds, woolen blankets in colors, 5 x 10, and for 9 rupees. They are all-wool too, and all of this is handmade. All sorts of woolen things, silk and cotton, for dirt-cheap prices. The only catch is a very heavy duty on such goods in the States. At that they are still cheap.

Where we are at present, parked on the river, the jumble of wooden houses built on top of walls along the river’s banks, look like rat traps. Still, it is a type peculiar to Kashmir and has its charms.

But to return to the leather shop—Frank looked for a pair of shoes and I bought some Chipaneeses (spelling?) for 5-8-0. They consist of a very thick flat sole of buffalo hide, and a crisscross of cowhide straps above, as a sandal, with a strap fastening back of your heel to keep your foot in. No sides at all to it. A cowhide soft leather sock is also worn. It comes to about an inch above the ankle and laces. On the bottom of the sole, little iron pyramid spikes are nailed in. This prevents the leather from ever wearing much, if it would ever wear much, prevents you from slipping except on stone where it helps you to break your neck. The thing is very comfortable and in the house you wear only the leather socks. The only hitch is that I paid 5-8-0 for mine and on the way home we saw some for 2-8-0 or 3-8-0. Well, maybe the leather in mine is better, but I doubt it.

Walked down the Bund and visited some of the leather shops trying to get a price on equipment for our trip to Leh. Tents 10×10, Rs. 10 per month, 4 pony baskets, waterproof, Rs. 3 per month, cots 2 Rs. per each a month. These latter are too heavy, so we shall probably use reed mats for beds. I have practically no clothes here except those I have on, and so will garb in a native costume for the trip.

Walked down the Bund and visited some of the leather shops trying to get a price on equipment for our trip to Leh. Tents 10×10, Rs. 10 per month, 4 pony baskets, waterproof, Rs. 3 per month, cots 2 Rs. per each a month. These latter are too heavy, so we shall probably use reed mats for beds. I have practically no clothes here except those I have on, and so will garb in a native costume for the trip.

We returned to the houseboat to discover that while Mort was in the living room, this kid hooked two blankets and my razor. He probably thought that my razor was gold, but all he got was a 79¢ special. Lussoo spent the afternoon and evening looking for him, but without success as the kid has probably hit for the hills. Also took a rupee’s worth of hard candy from Mort.

E.F. Knight in “Where Three Empires Meet,” says “That bearded athletic-looking disgrace to the human race” in speaking of the Kashmiri man. “Ganpat” writes, “Utterly devoid of courage in any form, moral or physical, the Kashmiri man, as a rule, possesses the whole gamut of mean qualities that go with such a lack of man’s first attribute. I once watched a Kashmiri quarrel between two boatmen—the river-boat life is a feature of Kashmir. The quarrel was sustained and bitter and supporters flocked to each side. Streams of high-pitched invective were poured forth, doubtless, in true Oriental fashion, concerned chiefly with the morals, or lack of morals, of the quarrelers’ womankind, much of it more probably true in Kashmir than elsewhere in the East. But, unlike most of these quarrels, this had an abrupt finale. Stung beyond bearing by the insults, one man at last seized the loose end of a cloth and with it deliberately flicked his opponent upon the shoulder. Amid a dead silence, the gathering broke up, shudderingly and furtively fleeing away to their boats, aghast of the spectacle of one man raising his hand against another.

“Not unnaturally, therefore, the Kashmiri does not rule himself. He has had many dynasties of rulers in the past, and the latest comers are the Dogras of Jammu—excellent fighting men and distinctly strong-handed rulers. In addition to holding Kashmir, they hold also the territories beyond, Baltistan and Ladakh, and are suzerains of Gilgit and Hunza Nagar, and thus the Ruler of Jammu holds the northern border of the Indian Empire.”