Sunday, November 3, 1929

They say every dog has his day. I had mine today. Things were not promising at the start for it had rained during the night—first in nine months so they say. Though it was not raining at six, the clouds were heavy and hung low, blotting everything from view and making clothes damp and uncomfortable.

Breakfast seemed a bit of a treat today and everybody lingered on a few minutes longer than usual. The reason was French toast. Personally I was more interested in the breakfast food, but didn’t fail to consume two shares of the toast. I sit at a very favored table where the mechanics—motor corps or whatever it is—sits. The point is that there are seldom more than 4 or 5 out of 12 present, thus leaving lots of extras for seconds.

By this time the clouds had raised and I went to the edge of Kilauea. Halemaumau lay dark and foreboding in its lake of lava. Clouds of steam issues from scores of cracks around the pit and scattered over the crater floor.

At ten I packed my toothbrush in the blanket and started on the much-looked-forward-to return to Hilo. After all, the effort of getting to the top is worth the coast down again. In all thirty miles I did not have to pump a mile. There should be thirty mile posts. I thumbed twenty-five and couldn’t find the other five. Same to them though.

A light drizzle at the start soon stopped and I really enjoyed life—tearing down the perfect road at 25 and 30 per, Mauna Loa cloud-covered behind me, small lava and cinder cones on its broad slopes, luxuriating fern forests flying by and the fragrant scent of lilies and the eucalyptus trees in the air—a smell of fresh earth and cane fields.

By stops and no pedaling I spread the trip out to two hours, arriving in Hilo at noon. Returned the bike and walked to the wharf. Returning by the same boat, the Haleakala.

The second whistle has just blown and the tug stands by to unhook the anchor chains fastened to float buoys. Steerage is crowded this trip. The second passenger aboard, I have a good seat on the end of a bench. However, many are sitting on their luggage or pacing back and forth on the crowded, luggage-littered after steerage deck. A few are down below in the bunk room.

First and second class passengers are being shown their staterooms by stewards uniformed in white. Now the boy is sounding the gong to warn visitors to leave the ship.

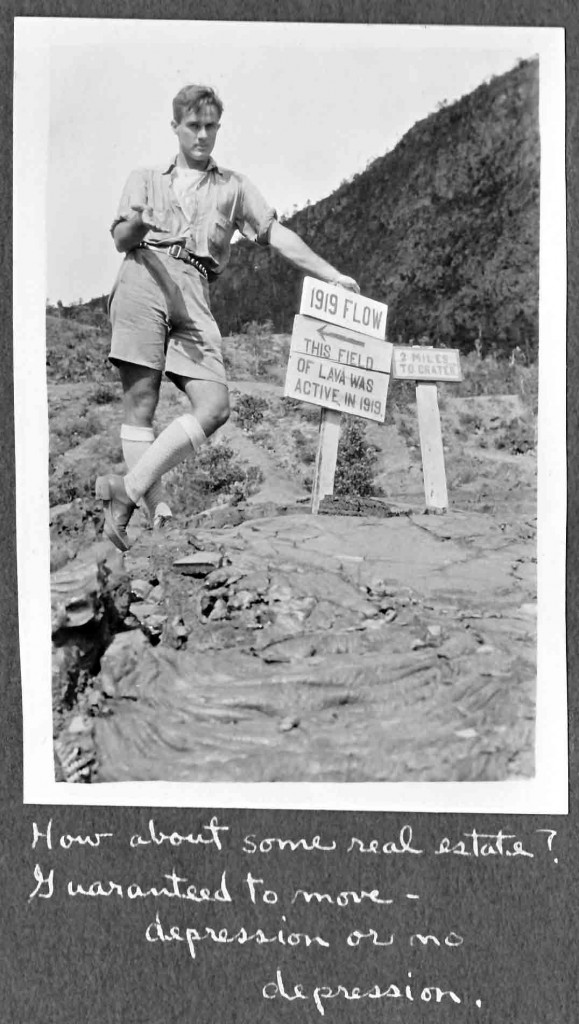

We steerage passengers are a curious-looking lot. For instance, here I am sitting on my half-unrolled blanket, writing. It only takes one glance to see I’m dirty—no doubt of it—good, honest, hard-won dirt and lots of it. My shoes are gray with clinging volcanic dust, socks brown with dirt and spotted with grease from the bike. Where sunburn gets off and dirt gets on is a mystery only soap and HOH [??–maybe H2O] can dissolve on my bare knees and face—yes—red nose! The shorts, filthy and spotted, still hang on me but don’t hang together. Unfortunately the seams have parted company on all four sides. Needless to say my shirt and jacket are comfortably dirty and les cheveaux full of Hawaii real estate.

The ropes are being drawn in now. In response to a whistle, the tug steams to the buoy and lets go the cable. The ship drifts from the dock. The railing is crowded on that side. People are all waving and calling to their friends. It is a colorful gathering that watches the ship gain speed as it leaves the wharf behind. On the left we pass Coconut Island, so famous in Hawaiian legends, now modestly assuming the romantic role of being the home of the Yacht Club and public bathing place. In ten minutes the Crescent City has slipped past and we are outside the long harbor breakwater.

Hilo means to twist. Its name originates in a legend—that Kamehameha once left a follower on the beach here with his canoe while he went into the country. When the time for the great king’s return was past, the retainer became uneasy and set out to look for his king, first securing the canoe to shore by means of a rope made of twisted ti leaves. When the king returned he was very surprised to find that ti leaves could be twisted into rope and said, “Let this place be called Hilo.” Just one of the scores of myths and legends that surround the volcanoes, towns, hills, rivers, etc. of Hawaii.

We are now sailing up the coast but a half-mile off the precipitous cliffs. The fresh green cane fields roll back in many irregular waves and knolls to a dark fringe of trees at the foot of Mauna Kea. Each village can be plainly seen as well as the road winding in and out of the many gorges. Mauna Kea is behind a rolling mass of somber gray clouds, Mauna Loa is also lost in clouds, but one can note every detail, seemingly every tree and house, on the long gentle slope of verdure that rises so gradually from the sea, pauses for a moment at Kilauea, then makes one last grand sweep upward to the magnificent heights of Mauna Loa. Out here the sea is a bit choppy and the ship is rolling. But why be bothered when there is such a lovely panorama to be seen shoreward—the surf dashing over the rocks at the foot of the cliffs—the gorgeous rolls of green interspersed with darker green forests, the valleys—Hawaii. (Nuf hot air for a while.)

Have just been talking to a petty officer who is returning to Schofield after a month’s stay at Kilauea Camp. He is returning two weeks early—tired of the place. Others say the same thing. His first-class fare round-trip with army reduction is $19.

As I have said, the steerage passengers are a curious lot. They are sprawled out over their luggage on the deck so it is hard to move around. The men seem to prefer khaki woolen shirts with khaki trousers—many with blue overall trousers as worn in the army and navy. There are those that wear a regular suit. Two such are in sight at present—one having a dark brown suit and light straw hat, the second an Irish-green coat with light flannels. The cowboy types that work on the plantations are much in evidence—overall trousers, extremely loud flannel shirt of large glaring designs, peaked hat with large flowing brim. Some of these hats are designed.

The women are tamer as a rule, though some stand out. One lying on a cape at my feet wears a black skirt, white blouse and white cotton stockings, all flowing, in other words seemingly a size of two-too large. A second crashes you with a brilliant shapeless green dress, a happy contrast (?) to her two little barefoot girls who wear equally brilliant red dresses. Most everybody wears one or more leis, some having a half dozen about their neck, submerging their chins, and others not only a neck full but an arm as well. These leis are of paper—all possible colors. And so it grows dark and so I’ll stop writing.