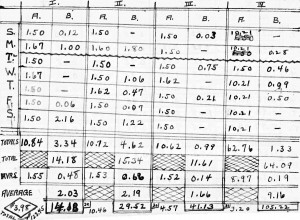

According to Hall’s final calculations, his 534-day journey cost $1,618.00 $1,617.95. (He recalculated after finding 5¢ in his pocket.) The average cost per day was $3.03; per country visited, $38.51; per mile—49,000 miles was his estimate—just about three-and-one-third cents.

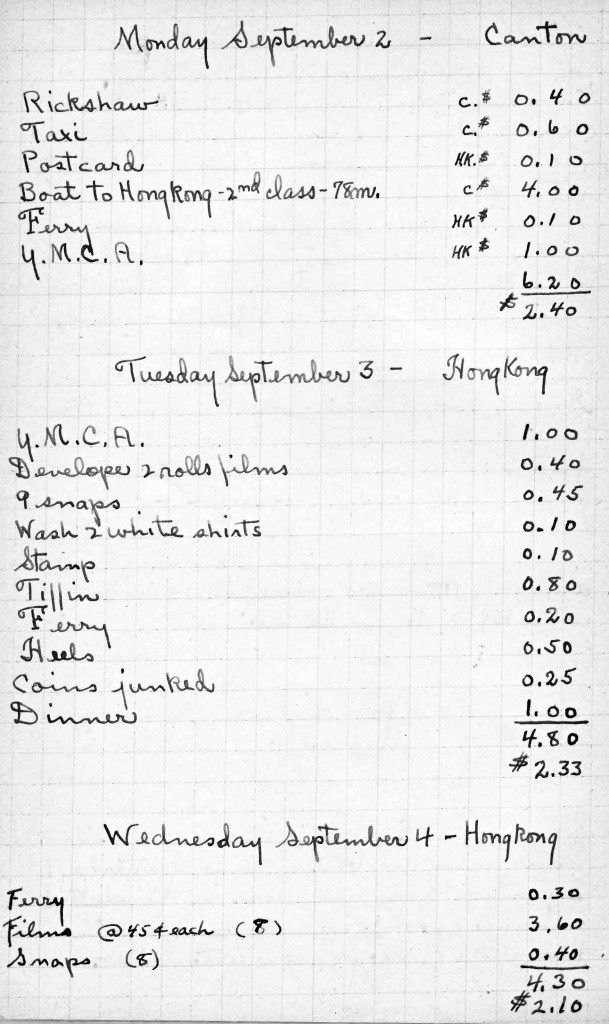

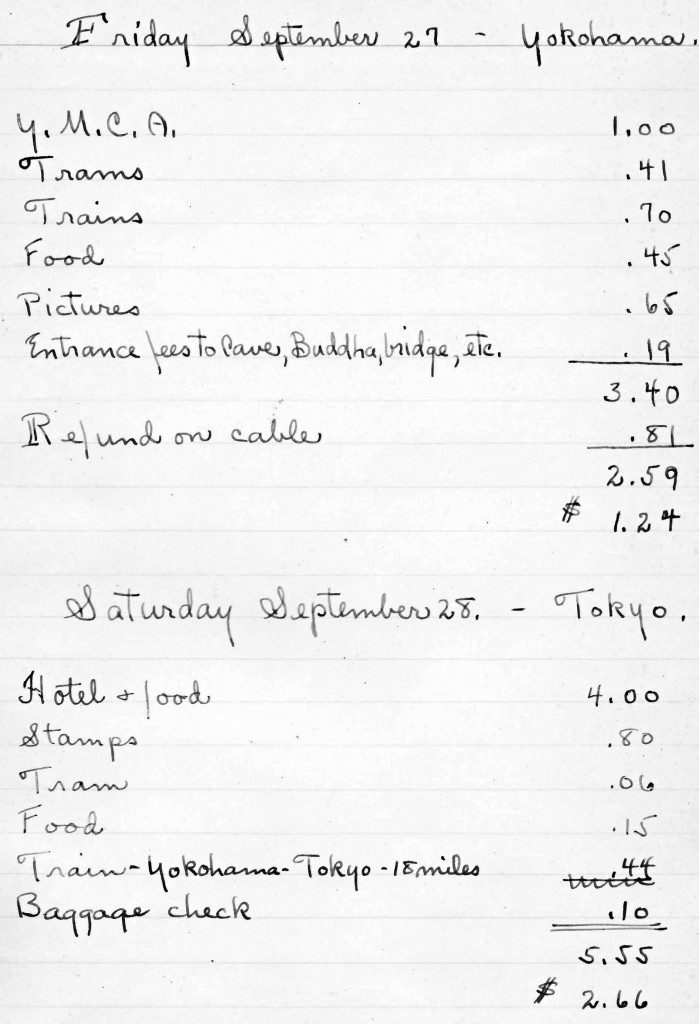

Each of the nine journals has a number of pages devoted to keeping track of Hall’s expenses. Here’s a typical example. Sometimes there are extra lists, charts, chicken-scratch calculations on the endpapers or in the margins. It’s pretty obvious right from the get-go that he was always planning ahead to try to make the most of his roughly $90 per month allowance, constantly thinking of ways to shave costs so he could go farther, see more, perhaps eat a little something that day? He’d plan nighttime train trips to save the cost of a hotel; sleep on park benches, in train stations, in haystacks to save the less-than-a-dollar cost of a room.

Transportation was a huge expense and, although he did not figure it separately, it probably sucked up about half of that $1,618.95. Traveling through Europe by bicycle was a cheap idea, but even that had hidden costs—bum tires, duties on the bike in just about every country visited (which I think were returned to him when he left the country, except in Spain), and charges for carrying the bike as railway baggage.

Transportation was a huge expense and, although he did not figure it separately, it probably sucked up about half of that $1,618.95. Traveling through Europe by bicycle was a cheap idea, but even that had hidden costs—bum tires, duties on the bike in just about every country visited (which I think were returned to him when he left the country, except in Spain), and charges for carrying the bike as railway baggage.

Later on, after the bike was gone (with no mention of what happened to it!), he walked. In Cairo he writes: I’m worse than a Scotchman. Walked 25 miles to save from 30 to 60 cents and would have walked the other 15 to save the two bits, but my feet were hurting. I wouldn’t trade it for anything, though. It was the best way of seeing how the country people existed. A couple weeks later: I seem to be the only person in Luxor who has a financial status so flat that even walking is a luxury because of the wear and tear on shoe leather. At least I am the only one that will admit the fact.

His possessions—never enumerated—cost too much to send from country to country by train as he traveled through Europe by bicycle, so he ditched almost everything in Berlin so that he could carry it all with him. The photographs give you an idea of which clothing remained.

Of the three shirts Hall mentions keeping, here’s the saga what happened to one of them, played out over a year later in Japan: I was feeling real noble this afternoon and decided to have my clothes washed while I could still get them off of me. The boy returned a few minutes later and by signs made me to understand the washing process would take a week. I hadn’t realized they were so dirty. Maybe he’s right though. But that makes me uncertain whether my shirt is made of dirt or cloth. If I rub it, the thing falls to pieces. A few days later in Nikko, Japan after seeing a busload of American tourists: Gosh, it’s painful to realize I’ll have to tumble into some respectable clothes in a couple of months. I feel better now, clothes dirty and worn out, shirt so rotten it is falling into shreds, not entirely rotten dirty. And a few days later on: I was going against all my ideas of comfort by wearing a coat—this occasioned by the fact that the shoulders of my shirt had fallen to pieces. A few days later: Had a final wash day and soaped up everything but the blankets—which don’t miss smelling. Discovered Frank’s sweater is brown instead of black and am at a loss as to where to hang my shirt—since it won’t stick to the ceiling nor stand up in the corner any more. And finally at the end of the happy-dirt period: We steerage passengers are a curious-looking lot. For instance, here I am sitting on my half-unrolled blanket, writing. It only takes one glance to see I’m dirty—no doubt of it—good, honest, hard-won dirt and lots of it. My shoes are gray with clinging volcanic dust, socks brown with dirt and spotted with grease from the bike. Where sunburn gets off and dirt gets on is a mystery only soap and HOH [??–maybe H2O] can dissolve on my bare knees and face—yes—red nose! The shorts, filthy and spotted, still hang on me but don’t hang together. Unfortunately the seams have parted company on all four sides. Needless to say my shirt and jacket are comfortably dirty and les cheveaux full of Hawaii real estate. Hall always looks so clean in the photos—maybe it’s a good thing they’re so fuzzy.

Hall didn’t use a lot of slang in his journals, but he did come up with a number of words for money: suds, cinders, kicks, bones, rocks, smackers, clinkers, berries, crackers, cartwheels, and my favorite, pluncks. Cute.

Hall didn’t use a lot of slang in his journals, but he did come up with a number of words for money: suds, cinders, kicks, bones, rocks, smackers, clinkers, berries, crackers, cartwheels, and my favorite, pluncks. Cute.