If you’ve discovered this blog, it might be because you googled Hall Lippincott rather than Lippincott Hall—a residence hall at Rutgers and also the name of the law school building at the University of Kansas. Sorry, not related. What we’re doing here is publishing the travel journals, kept so meticulously by our father, Hall Lippincott, as he pedaled, sailed, and hoofed his way around the globe some 80 years ago.

Hall didn’t intend to make it around the world in the proverbial 80 days—he managed to stretch it out for 534 days, traveling more-or-less 49,000 miles, and technically touching a toe in 42 countries—or at least having a really good look at a few of them from a short albeit uncrossable distance. This was a time when lucky college grads were shipped off to Europe and beyond by parents who could afford to underwrite such a trip—a few months or so abroad to broaden their minds and sensitivities before returning home to the realities of their first real job, their first real marriage, the inevitable baby or two, and—in this particular decade—the overarching, difficult realities of the Great Depression, Europe and Japan’s apparently unstoppable descent into the horrors of racial profiling and fascism, and the resulting World War II, which shuffled the balance of real and imagined power across the globe and swept away the world that Hall worked so hard to document.

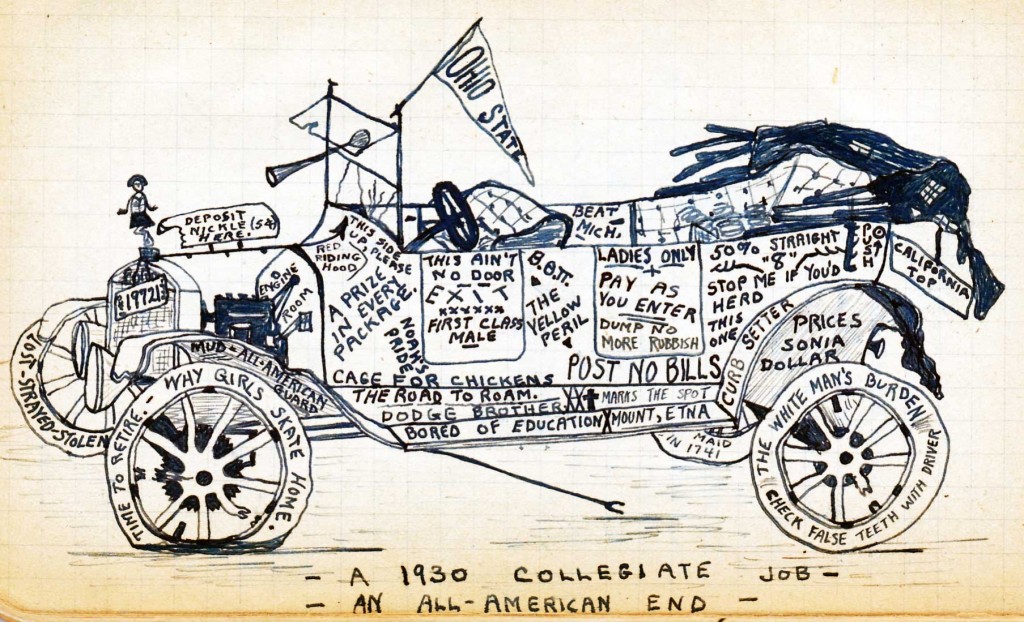

Born in St. Louis, Missouri,  raised and educated in Cincinnati and Columbus, Ohio—a Beta at OSU—Hall left the family home in Wilmette, Illinois, on July 10, 1928, returning as a well-timed mother-pleaser on Christmas Day, 1929. His parents—Dick (Richard Rudderow Sr) and Martha (Mayme Chenoweth Hall) Lippincott got a good return on their investment—a too-well-tanned (as would later become apparent), fit, friendly, self-confident, yet modest young man, ready to meet absolutely anything life threw his way. Dick’s investment was also modest, as far as 1920s globe-trotting went—$3.03 per day, all inclusive. It’s surprising, frankly, that Hall didn’t furnish per-mile and per-country figures as well as that average—he was always blessed, or cursed, by an inescapable, distracting attention to detail. (See the page entitled Money Mattered. . .a Lot.)

raised and educated in Cincinnati and Columbus, Ohio—a Beta at OSU—Hall left the family home in Wilmette, Illinois, on July 10, 1928, returning as a well-timed mother-pleaser on Christmas Day, 1929. His parents—Dick (Richard Rudderow Sr) and Martha (Mayme Chenoweth Hall) Lippincott got a good return on their investment—a too-well-tanned (as would later become apparent), fit, friendly, self-confident, yet modest young man, ready to meet absolutely anything life threw his way. Dick’s investment was also modest, as far as 1920s globe-trotting went—$3.03 per day, all inclusive. It’s surprising, frankly, that Hall didn’t furnish per-mile and per-country figures as well as that average—he was always blessed, or cursed, by an inescapable, distracting attention to detail. (See the page entitled Money Mattered. . .a Lot.)

Hall’s companion for the first month or so was his St. Louis cousin, Jack Lippincott. (He and the other major players are discussed in more detail in the Hall’s Friends section.) Jack and Hall’s pie-in-the-sky idea was to buy a cheap motorcycle in England and tour the continent in comfort, but they quickly realized that all they could afford were bicycles. Hall doesn’t say very much about how Jack fared, so it might not have been a very fun trip for him. They traveled on the extremely-cheap—with luck Jack might have managed to get more food than Hall did. Jack went home from Paris. Was that always planned? Sorry, but we never thought to ask. We didn’t know Jack or his side of our family much at all thanks to one of those senseless family quarrels that tore Dick and his brother (and their extended families) apart.

Hall continued on around Europe with his untrustworthy bicycle, burrowing into haystacks at night, filching apples and potatoes from farmers’ fields, cooking plum soup with cabbage gravy in his little pot, trying to sleep and eat on less than a dollar a day.

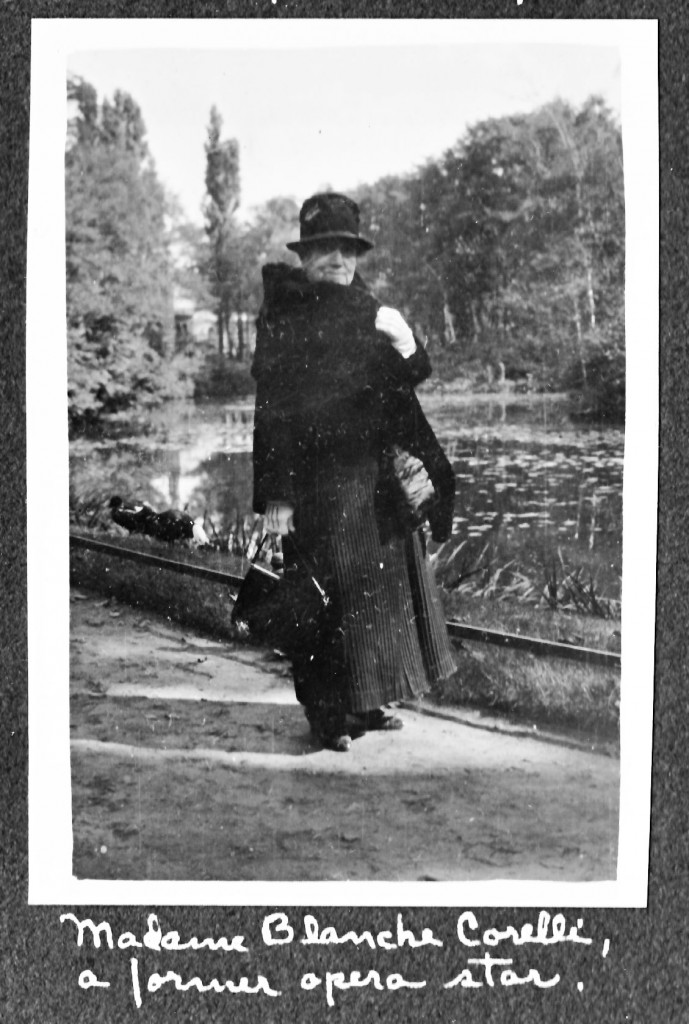

He was adopted, along the way, by some really interesting people— Madame Blanche Corelli (75 years old) picked him up at Deutsche Bank in Berlin, fed him for a few days, regaled him with stories of her operatic career, her friends and relatives such as Harry Houdini, Enrico Caruso—and then remained a friend and the beneficiary of Hall’s modest and sporadic financial support up until 25 September 1939 when we think/hope that she died before Nazi Germany was able to kill this talented Jewish lady. . .but Hall never knew for sure—Mme’s replies to his letters simply stopped coming. In mid-January 2011 we completed a web site about Mme Corelli, showcasing the 72 letters she sent to Hall that document what were probably the last nine years of her life. Please have a look! http://corelli/halllippincott.info/

Madame Blanche Corelli (75 years old) picked him up at Deutsche Bank in Berlin, fed him for a few days, regaled him with stories of her operatic career, her friends and relatives such as Harry Houdini, Enrico Caruso—and then remained a friend and the beneficiary of Hall’s modest and sporadic financial support up until 25 September 1939 when we think/hope that she died before Nazi Germany was able to kill this talented Jewish lady. . .but Hall never knew for sure—Mme’s replies to his letters simply stopped coming. In mid-January 2011 we completed a web site about Mme Corelli, showcasing the 72 letters she sent to Hall that document what were probably the last nine years of her life. Please have a look! http://corelli/halllippincott.info/

Hall met young George Nakashima on the ferry to Sicily and they bummed around together for a couple of days, staying up talking all of one night because their 3rd-class beds were so bed-bug-infested they didn’t want to use them. A few days later, the Italian Arctic explorer Umberto Nobile signed Hall’s passport, apparently not a capital crime in those days. [Well, a little more research puts the kibosh on that idea—click on the Hall’s Passport page on the very top line of the Homepage to read more about this fascinating polar explorer and see why he might not have signed the passport. . .]

Hall met young George Nakashima on the ferry to Sicily and they bummed around together for a couple of days, staying up talking all of one night because their 3rd-class beds were so bed-bug-infested they didn’t want to use them. A few days later, the Italian Arctic explorer Umberto Nobile signed Hall’s passport, apparently not a capital crime in those days. [Well, a little more research puts the kibosh on that idea—click on the Hall’s Passport page on the very top line of the Homepage to read more about this fascinating polar explorer and see why he might not have signed the passport. . .]

In Sintra, Portugal, a countess showed Hall around; in Gibraltar he was swept up into the frenetic social network for a month, a handsome and willing extra at dinners, picnics, dances, Uncle Hall to the cute kids. Here’s another question we never asked—how could he afford to keep such company on such a tight budget?

In Luxor, Egypt, Hall was taken in by a nutty German antiquities thief, a sad, scary fellow who slept with an statue stolen from King Tut’s tomb before the artifacts uncovered there just a few years earlier had all been spirited away to safety in the museum at Cairo. Hall and his traveling companions were invited to join a maharajah’s ten-day-long hiking party in India; in Canton and Shanghai he had introductions to Americans or Europeans living there and was readily folded into their lives and entertainments; and on and on. People liked Hall and wanted to help him along, people from all walks of life and of all means. The world was a much smaller place back then and it’s amazing how many of the people he met along the way, when googled, pop up as movers and shakers of their day or young men destined to be famous.

After Jack left from Paris, Hall traveled alone, but had the good luck in Jerusalem to make two new friends, Mort Hartman and Frank Aldridge, who were cycling around the world and writing about it, Mort for the Greenville (South Carolina) News and Frank for the Tulsa World. The trio stayed together through Egypt, India, and Kashmir, splitting up to let Mort stay behind in India to recover from something he picked up along the way. No, not that kind of thing—these boys were real innocents abroad—but an inevitable bacterial infection because they ate anything, drank everything, slept anywhere, traveled 3rd or 4th class when allowed. (Europeans were not usually allowed to travel with the natives in the East, although Hall circumvented this nonsense whenever possible. It was lots cheaper.)

He forged on alone to Ceylon, Straits Settlements, Federated Malay States, Siam, French Indo-China, China, Hongkong, and Japan. (How many kids under 45 can even find all of those places on a map!!??) In Hawaii, broke and waiting to get a job on a freighter heading for the USA, he hooked up with Chicago friends, whose swell social life made him wonder whether or not he ought to move there some day. When he finally landed in New Orleans, Hall’s first thought was to get back to Jean McCampbell, the girl he’d left behind in Columbus, Ohio; we consider ourselves very, very lucky that their romance fizzled and we wound up, six years later, with the best mother that he could have picked out for us.

After Hall returned home to an economy in free-fall, we’re not entirely sure about everything he did to make ends meet until he met our mother, Dorothy Agnes Darby in 1934, marrying her before a year had passed. We have a shiny badge issued by Evanston, Illinois, where they lived initially, Peddler No. 1. That meant he was selling something door-to-door. We think he worked for a brokerage firm for a while and also for Marshall Fields in their wholesale department. He eventually wound up following his father and grandfather into the insurance adjustment business, a career that occupied his body, but not his soul.

After Hall returned home to an economy in free-fall, we’re not entirely sure about everything he did to make ends meet until he met our mother, Dorothy Agnes Darby in 1934, marrying her before a year had passed. We have a shiny badge issued by Evanston, Illinois, where they lived initially, Peddler No. 1. That meant he was selling something door-to-door. We think he worked for a brokerage firm for a while and also for Marshall Fields in their wholesale department. He eventually wound up following his father and grandfather into the insurance adjustment business, a career that occupied his body, but not his soul.

Aside from travel (and Dorothy), Hall’s main passions involved keeping track of things, categorizing them, collecting things, stuff like that. Like his grandmother and dad, he was a meticulous stamp and coin collector; he lettered in golf for two of his college years and played every chance he got until it was just too difficult; everything in his drawers was just-so. When he discovered fossicking—rock collecting—every outing and vacation was geared  toward that pursuit. Our mother might have been the catalyst for their wonderful seashell collection, but she was not the one out there wading in Sanibel’s mosquito-filled shallows to find live King’s Crowns by stepping on them. Then they discovered that their rock-shop friends were trading telephone pole insulators and suddenly every trip—U.S. and foreign— was centered about this new thing. There was something else up on those cross-arms, though, and after Hall fell off his home-made ladder, they bought a binocular so they could safely identify the insulators. . .and the hawks.

toward that pursuit. Our mother might have been the catalyst for their wonderful seashell collection, but she was not the one out there wading in Sanibel’s mosquito-filled shallows to find live King’s Crowns by stepping on them. Then they discovered that their rock-shop friends were trading telephone pole insulators and suddenly every trip—U.S. and foreign— was centered about this new thing. There was something else up on those cross-arms, though, and after Hall fell off his home-made ladder, they bought a binocular so they could safely identify the insulators. . .and the hawks.

Birding trumped just about everything else. The ideal hobby for Hall and Dorothy, it could be done 24/7 absolutely anywhere in the world, at any level of expertise, the field guides were a delight, the strategy a constant challenge, and it was a lister’s paradise. Did I mention that they loved actually looking at birds, too?

Hall and Dorothy made umpteen trips after their kids had fledged, most of them road trips to Mexico and farther south, but several journeys to Europe, New Zealand, Australia, and Alaska, the latter still exotic enough in the early 1970s to be considered a foreign country by most of you Outsiders. Yeah, “umpteen” is not a recognized quantity, and I could go over to the bookshelf and pull out the detailed log Hall kept of their vacations since 1935 to count them up, but I’d rather not.

Did I mention the years spent making scale-model wharves and “western” scenes, shell mirrors, Petoskey stone jewelry, tumbling agates found on dozens of trips to Winona, and cleaning fossils from the Peabody Coal Mine south of Chicago? They paid for their trips—he knew because he kept careful track of it—with the money made by selling these creations.

Who had time left for work?! Hall retired in about 1980 and moved from Winnetka, Illinois, to Colorado Springs in 1983. (He and Dorothy had lived in Grosse Pointe, Michigan from 1939 to 1961.) Hall died in 1991. Yes, there were two children—not the three kids he writes about in one journal entry—but the compensation was three loving grandchildren and a bunch of great-grandchildren that he unfortunately never knew, but would have approved of and folded snugly into his world.

When I was small, he told me bedtime stories—carrying the action forward for years and years—about Cynthy (and Julie Beach, or whichever girlfriend was spending the night with me) who traveled around the world, having his adventures, word for word, line for line. The journals were readily available to my brother and me—and every year or so Dad would re-read them himself. In my child-mode, I always felt sorry for him, stuck in flat old Michigan with a wife and two kids and a job that sounded realllly  boring, not picking the bugs out from between his teeth in Hungary or cutting his foot in the Taj Mahal reflection pool, not being free. I wanted so badly to do what he had done—to just take off and be my own boss—that I imagined that he regretted having to come back to Earth in 1929 to face realities, acquire and support a family, watch his parents grow old and die, and eventually do so himself without having the chance to fly unencumbered again. But I was wrong—he wanted his kids to fly. He had found the love of his life, the woman who was worth settling down for. It wasn’t always all roses, but it was his life and—in sum—our father was an unusually, even extraordinarily happy, contented man.

boring, not picking the bugs out from between his teeth in Hungary or cutting his foot in the Taj Mahal reflection pool, not being free. I wanted so badly to do what he had done—to just take off and be my own boss—that I imagined that he regretted having to come back to Earth in 1929 to face realities, acquire and support a family, watch his parents grow old and die, and eventually do so himself without having the chance to fly unencumbered again. But I was wrong—he wanted his kids to fly. He had found the love of his life, the woman who was worth settling down for. It wasn’t always all roses, but it was his life and—in sum—our father was an unusually, even extraordinarily happy, contented man.

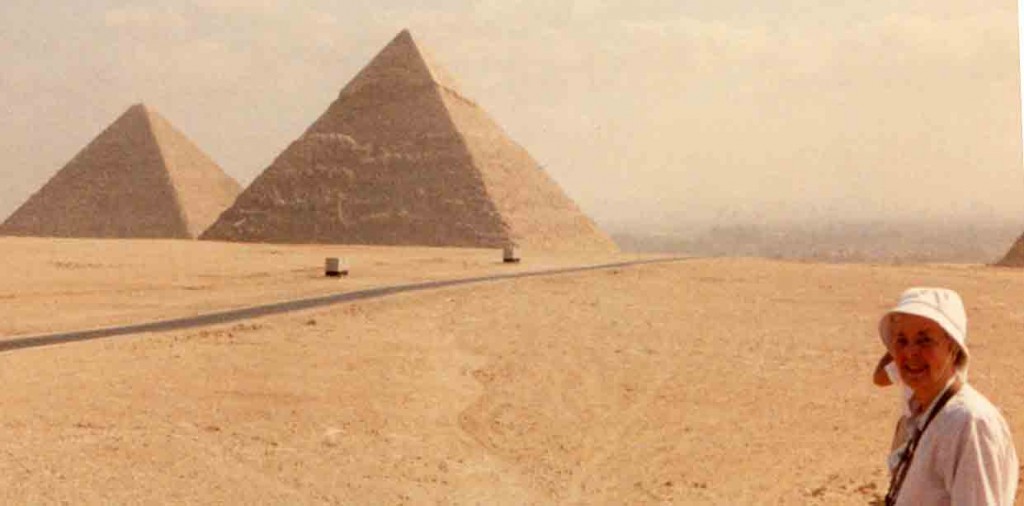

Hall returned to India in 1979, aside from Europe the only place he wanted to visit again. The year after he died, Dorothy carried his journal #3 back to Egypt, trying to capture some of the magic and awe he felt, reading his words nightly for clues.  She soldiered on until 2006, coaxing her kids to accompany her all over the world, always birding, always curious, creating her own unwritten journal of what she referred to as the next compartment of her life—life without Hall, life with just us.

She soldiered on until 2006, coaxing her kids to accompany her all over the world, always birding, always curious, creating her own unwritten journal of what she referred to as the next compartment of her life—life without Hall, life with just us.

Hall wasn’t much interested in learning how to use a computer, but we wouldn’t have done this web site unless we felt that he’d get a kick out of it. He became a different person than you’ll meet in the journals, and I don’t really understand why. I never saw him read anything other than the newspaper, Erich van Daniken’s strange but intriguing books and their ilk, the Bible, a Spanish-language grammar, and—over and over—his current favorite bird field guide. He talked anecdote, not philosophy. He rarely talked about himself. He was not at all pugnacious. He never proselytized. If he felt judgmental, he generally–but unfortunately not always successfully–worked hard to keep his mouth zipped shut about it. He was supportive, generous, calm in a crisis, loved liver and non-absorbent little pancakes with peanut butter and genuine maple syrup. He always ate the burned toast. He always smiled. He didn’t seem to enjoy socializing, but was happy to spend time with his few close friends and family. And I never saw him sketch a blessed thing such as he did for his journals, a talent he honed in response, we think, to cheers from the home team after they received the first journal with its tentative drawings. Just wait until you see what he accomplished in Egypt!

And speaking of that—it’s very likely that he pretty much copied some of the more out-of-context sketches—the flappers and the meant-to-be-comic figures you’ll see in #5, his Saigon Comics—but I have no idea what the original sources might be and cannot properly acknowledge them. I’ll add citations if pointed in the right direction. Hall, Mort, and Frank shared photos—and a number of Hall’s wonderful Egypt photos were given to him by Ahmad Yousef—but his point as well as mine is getting the story across without a lot of fussing about the details and if his camera did a lousy job, he’d gladly use someone else’s snaps. I have corrected only the stuff that drove me nuts: replaced thot with thought, thru with through, further/farther, added umpteen commas, took the extra days out of September and November, put my explanatory though occasionally snitty comments in [brackets], and left in the more endearing of his misspellings. You’re definitely on your own with the French–even if you don’t speak a word, it’s possible to struggle through with at least 50% comprehension, and if you can’t even manage that, you haven’t missed a lot anyway.

I have not deleted 98 percent of Hall’s prejudices and politically incorrect statements; he didn’t voice them any longer when I knew him. We are all children of our times, like it or not. We record what we see and understand as best we can through the mind and heart of the person that we have so far become. . .and then we move on.

What a great project you have undertaken, one that will be appreciated far beyond the Lippincott family. I look forward to reading his journals and experiencing the world from a perspective that is no longer.