Monday, April 22, 1929

Didn’t move a muscle last night. The waiter woke me up at seven for Chhoti Haziri which he served in the room. After obtaining a pass from the magistrate, we followed the hilly, winding roads to Dilwara Temples. They are enclosed by a wall and several old buildings. The roofs of the temples, those parts that have roofs, look very old—in fact, from the outside one would guess the place was a stable. As they are open to visitors only from noon till six, we had to wait in the waiting room nearly an hour. The visitors’ book contained names of people from all over the world, most by far from America. Many raked the guides, and slippers required to be worn, over the coals. Others told long hard-luck stories of how they were mistreated. Scores waxed poetical and elegant while numerous Americans cracked wise. A few of the comments were:—”The cat’s meow.” “All’s well, all swell.” “Beautiful but dumb.” “Mrs. Bigfeet, got them very dirty.” One man wrote, “The guide can not even speak Hindustan.” The following day somebody added beneath, “Not surprised since hearing you speak it yesterday.”

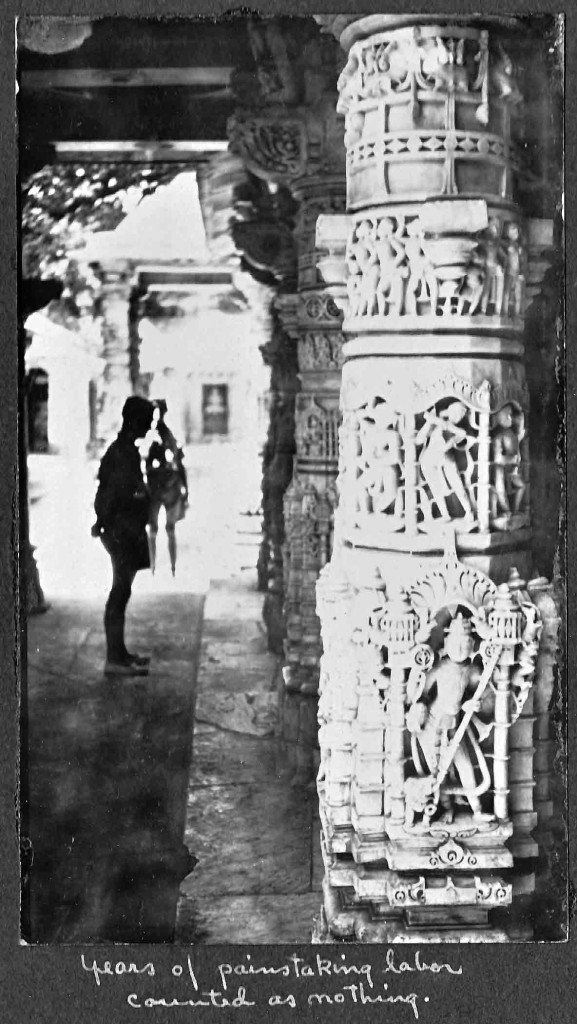

Canvas slippers were furnished us and off we went, led by a sprawly soldier guide with a wicked-looking moustache. Entering through a door from an open courtyard we came upon a bewildering temple of carved marble. The principal object here, as elsewhere in Jain temples, is a cell lighted only from the door containing a cross-legged, seated figure of the Jina to whom the temple is dedicated—in this instance Rishabhanath, or Adinath. The cell terminates upwards in a sikhara, or pyramidal roof. To this, as usual, is attached a mandapam, or closed hall, and in front of this a portico, in this instance composed of 48 free-standing pillars; and the whole is enclosed in an oblong courtyard, 128 ft. by 75 ft. inside, surrounded by a double colonnade of smaller pillars, forming porticos to a range of cells, as usual 52 in number. Here, though, each cell is occupied by one of those Jinas that belong both to Jainism and Buddhism.”These are all so nearly identical as to be almost indistinguishable, and all have a shallow, meaningless expression. Their eyes flash from the semi-darkness of the cells. In other religions there may be several chapels attached to one building, but never 52. With the Jains it seems to be thought [that] the most important point [is] that the Jinas, or saints, are honored by the number of their images, and that each principal image should be provided with a separate abode.

Inside this main cell in the center of this courtyard, priests, women, and children were raising lots of noise praying and performing religious ceremonies. Pillars, arches, walls, and ceiling are entirely covered with carving, extremely intricate and well done. The amount and detail are almost unbelievable—and worked in marble—”hot stuff!” as Frank remarked. The sculptures represent different gods, etc., each figure in a different position, some of Ganesh represented as an elephant, etc. in endless procession—sailboats, ducks, warriors, and people being trampled under by elephants and passing throngs.

Inside this main cell in the center of this courtyard, priests, women, and children were raising lots of noise praying and performing religious ceremonies. Pillars, arches, walls, and ceiling are entirely covered with carving, extremely intricate and well done. The amount and detail are almost unbelievable—and worked in marble—”hot stuff!” as Frank remarked. The sculptures represent different gods, etc., each figure in a different position, some of Ganesh represented as an elephant, etc. in endless procession—sailboats, ducks, warriors, and people being trampled under by elephants and passing throngs.

Just outside the entrance door is a shrine containing a number of beautifully done elephants, a meter in height. A flight of steps leads to another temple, very similar to the first, but a little newer, having been built in A.D. 1230 and the other in A.D. 1031. This older one stands almost unrivaled for minute delicacy of carving and beauty of detail, even in the land of patient and lavish labor. The second is “simpler and bolder, though still as elaborate as good taste would allow in any purely architectural object.” At one end of this courtyard is a large elephant shrine. I notice a third temple on the way out that appeared well-carved in just the glimpse I had of it.

When we had our shoes on again, our guide fell in at the door for his tip, together with two others we had not yet seen. The guide was terrible, spoke no English (not necessary), but made no attempt to make it interesting for us or to point out objects of special beauty—just accompanied us in a disinterested manner. As American tourists are far too generous, in fact very foolish with their tips, he was undoubtedly expecting a couple of rupees—and he got 6 annas, just 5 annas 3 pies too much, the one pie being for wear and tear on his bare feet. Imagine we were roundly cussed and cursed, condemned to hell and recommended for annihilation by the Evil Eye, as we waltzed down the path toward the main road.

When we had our shoes on again, our guide fell in at the door for his tip, together with two others we had not yet seen. The guide was terrible, spoke no English (not necessary), but made no attempt to make it interesting for us or to point out objects of special beauty—just accompanied us in a disinterested manner. As American tourists are far too generous, in fact very foolish with their tips, he was undoubtedly expecting a couple of rupees—and he got 6 annas, just 5 annas 3 pies too much, the one pie being for wear and tear on his bare feet. Imagine we were roundly cussed and cursed, condemned to hell and recommended for annihilation by the Evil Eye, as we waltzed down the path toward the main road.

After lunch the Finance Minister of Alwar asked at length about America. He is in Abu to fix up a place for his Maharaja to stay soon, more than likely. He too is a Raja and takes charge of Alwar State during the absence of the Maharaja. This latter will be in Abu May 2nd or thereabouts—the Raja has asked us to Alwar so he can show us the things of interest.

Mort and Frank took a nap while I took a nice long walk to Sunset Point, a couple miles from the DB. Mt. Abu is 3,800 ft. above sea level and lies in a hilly bowl under mountain peaks. From Sunset Point you can look down on mountains below and two meandering rivers in an endless plain stretching out to the Rann of Cutch, over 100 miles to the west, and broken only by several huge mountain ranges jutting from this bushy plain. Then I followed a Baylay’s Path around the side of a mountain and came out high above the Nakki Lake, a fine body of water, artificial, overhung by a curious rock that looks like a gigantic toad about to leap into the water.

Returned by way of Bazar shortly after 8PM when the moon was on the water. Clouds of the afternoon disappeared and left the air cool and refreshing.