Wednesday, August 14, 1929

The weather improves. It has rained practically all day long. As no mail appeared on the scene today, I wired to find out if or when. The damages were heavy—one piastre per word, six for the six words I sent—$3.00. Also found I could get a boat from here the twentieth, a Messageries Maritime affair, the Spinx, for Hongkong. Where I can only go first on the Chinese boats, I can go third here, which pleases me more. The hold-up here is £6 with food. Leaves the twenty-third, which means eight more days in Saigon.

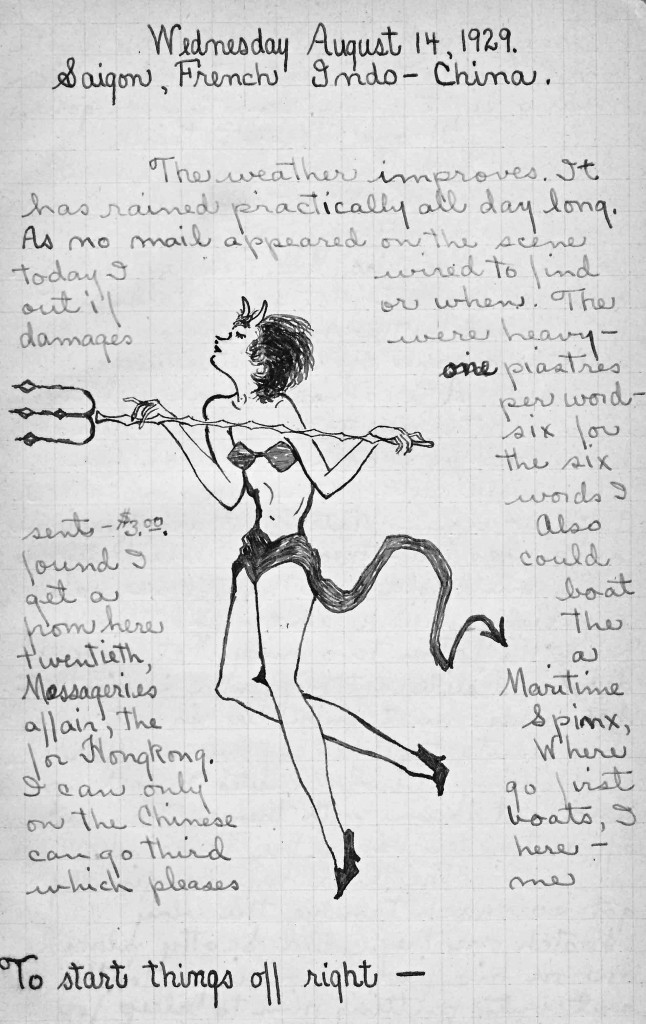

If one doesn’t think that Saigon is like Paris, walk down along the river front and up Boulevard Charner and the mob will descend. Mme. Paris, Mlle. French, Mlle. Saigon, and all the rest just as in Paris, but here called by the much more artistic name of Congaï.

After dinner I took a long walk. Returning to the hotel, I was waylaid by a commotion on the side-walk café of the Saigon Palace. I knew immediately that an American ship was in—two men wrestling on the ground told me that. One was especially drunk and more than kept the other two busy. Not only did he dislike sitting in a chair, but he needs must unbuckle his belt so his pants kept falling down. After watching a few minutes I went up and sat down with them. They were off a tanker bound for Touraine.

The third member finally got so much trouble, the very Scotch one they called Scotty placed one on his jaw, knocking a tooth out, but putting him to sleep for a quarter-hour. That time was spent in a more or less disconnected assurance that the big one had a book on navigation that was so simplified that a person with an active mind like I had, and a good education like I probably had, could learn to navigate in two weeks. But a person like Scotty, who wouldn’t study and also did many other things, wouldn’t ever learn. Scotty contested the point that my education could be better than his friend’s, and there was much discussing that. It’s a good thing that the onlookers didn’t know English or they might have had many blushes for all three were accomplished swearers with a much wider variety than the English tommies use.

Next they began to feel sorry for Pete, who also had a bloody nose. It was always “Wad er ya goin’ to do with a man like that? You can’t shoot him. The law protects him. Aw, I feel sorry for ‘im. I wouldn’t hurt ‘im and I wouldn’t let Red hit ‘im and Red wouldn’t let me hit ‘im. But what are you goin’ to do with ‘im? I had to hit him—but it was hard on me. He’s our shipmate, you see, and ya can’t hit a buddy, can ya?”

And so they both rambled on till Pete came to and started up. There ensued another tussle in which Red was lamenting how hard he had twisted Pete’s arm—nearly threw his shoulder out of joint, etc. Well, Pete’s arm hurt and he began to cry, so up hops Scotty to neck him and kiss him. In the meantime they had ordered a beer for me.

Another pants session followed and in the end Pete got to another table and sat down—till he fell off the chair. Red and I went into the bar where he bought a bottle of port and toasted. I thought it was a good time to be leaving, before the café closed and my friends would want to stow Pete in my room for the night. They were very insistent that I stay and it was only after Scotty had spieled on at length about how he was from Scotland, name McConnell, and all his family history, showed me a big jagged scar on his stomach from the war, and told me what a dirty deal Scotland had had from England, that I finally pulled out.