Monday, September 2, 1929

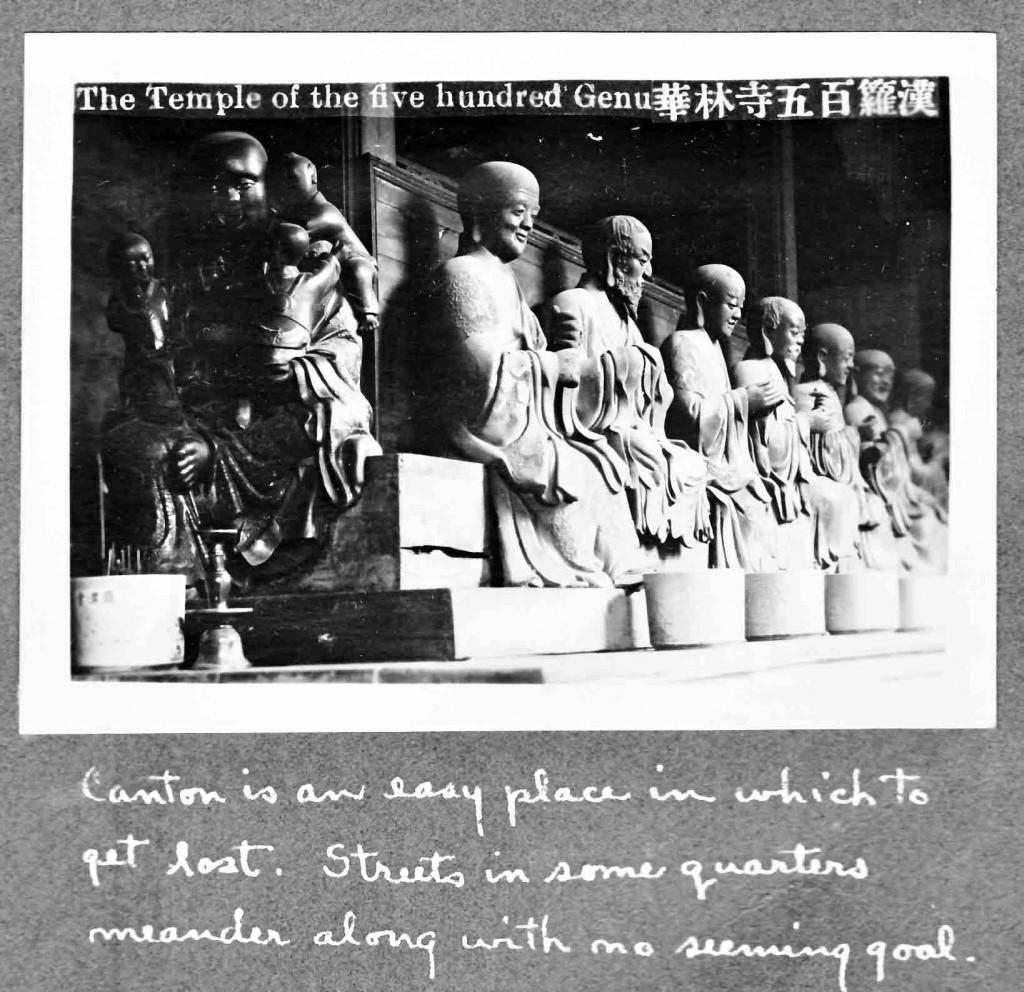

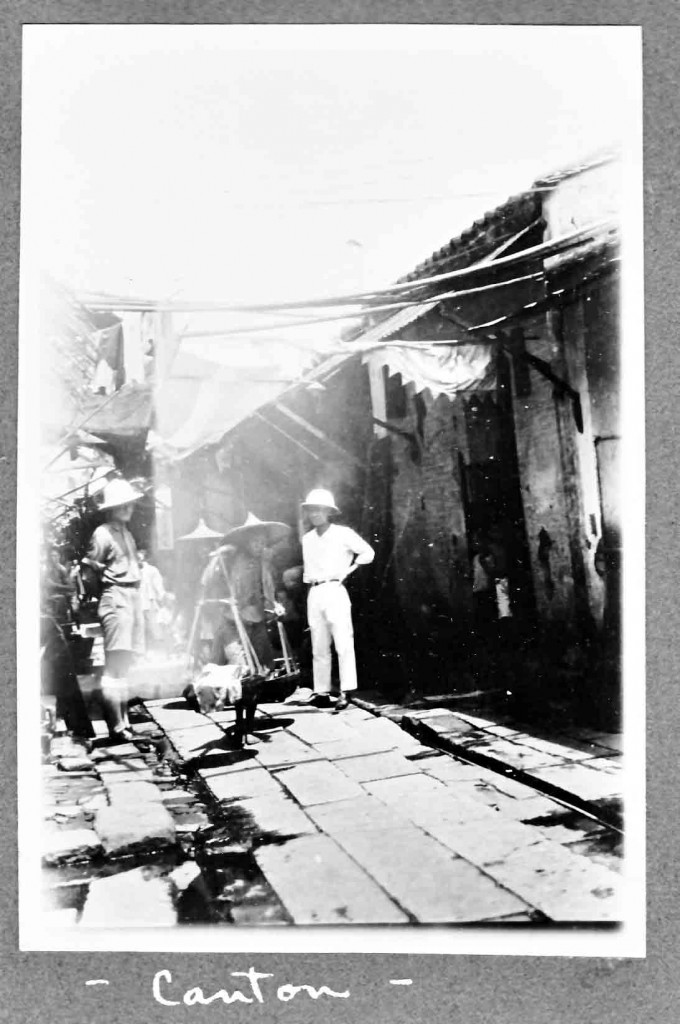

This morning after breakfast with the Karchers, Mr. Sauer and his assistant took me out to see more of Canton. It is one place I would hire a guide unless I had a week to see it in. Devilish hard to get where you start out for.

First we went down to the foreign concessions, going by way of these twisting streets. In one section were many large public houses where prostitutes lived. These burn down every year or so, so it seems, but new ones immediately replace the old.

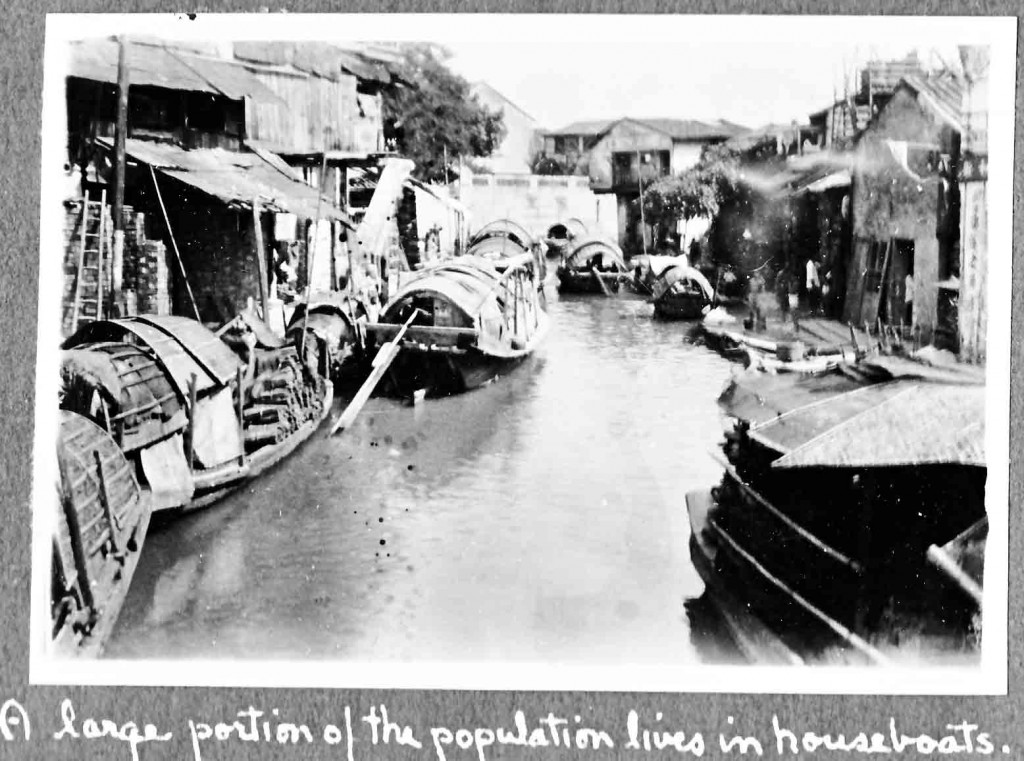

The foreign concessions are known by a Chinese name easy to say but hard to remember. The place is a good-sized island in the river—an island by virtue of a wide canal filled with thousands of sampans separating it from the mainland. A large part of the population lives in boats on the river and canals—don’t recall the figures but I’m sure it’s more than 50,000. All types and sizes of sampans and junks are jammed tightly in the canals, leaving only one third of the width clear for through traffic.

The foreign concessions are known by a Chinese name easy to say but hard to remember. The place is a good-sized island in the river—an island by virtue of a wide canal filled with thousands of sampans separating it from the mainland. A large part of the population lives in boats on the river and canals—don’t recall the figures but I’m sure it’s more than 50,000. All types and sizes of sampans and junks are jammed tightly in the canals, leaving only one third of the width clear for through traffic.

The foreign concession is allotted to the British and French, divided off into four squares. Germany lost her section and has established a new one at the north edge of Canton. The Americans have some banks, etc. in the British and French ones and the Consulate is in the latter territory.

Here there are no streets. Sidewalks are placed where they would normally be, and the street space is of grass and trees. A large park skirts the river front. The Americans have some land and a colony across the river, and a gun boat parked nearby to see that it doesn’t stray—just as the British have a gun boat in front of their section of the island to see that it doesn’t float down the river.

Just across the canal is the Bund, a wide street supporting much of the business and most of the large buildings. We went up in one of these to get a good view of the river. As large as this river is, just try to find it—literally covered with boats of all sorts. Smaller craft are packed in toward the river banks a hundred feet deep. It is amusing to see the larger of these that ply up and down the river; they all fly red flags, many of them with large characters in white. These are treaty flags to show that this particular boat pays a tribute to certain towns and villages along the river—otherwise the boat would be attacked and the goods stolen.

Taking a bus across town, I was surprised to see some soldiers order all the passengers but us out at one of the stops. This is to search them for guns, bombs, etc. Such a pleasant, peaceful city!!! Every so often the [rebels?] start to make things lively for everybody. Sometimes it is an armored car spitting fire as it tears along the street—sometimes they rise up and make it hot for most everybody. It seems [that] out in the district by the college they had a list of those homes they were going to raid and sack—all according to the wealth possessed. Knowing the missionaries were poor, their homes were not near the top. Whenever trouble starts, many head for the college for as a rule it is not molested, though bullets often fly through upper storey windows. These outbreaks are liable to occur any time. The last was about a year ago.

This section was a poorer one and many houses of only one small dingy room had no screen to keep out the ghosts. But the walls were plastered with large paper pictures of deities. Most of the children had large sores all over their heads.

This section was a poorer one and many houses of only one small dingy room had no screen to keep out the ghosts. But the walls were plastered with large paper pictures of deities. Most of the children had large sores all over their heads.

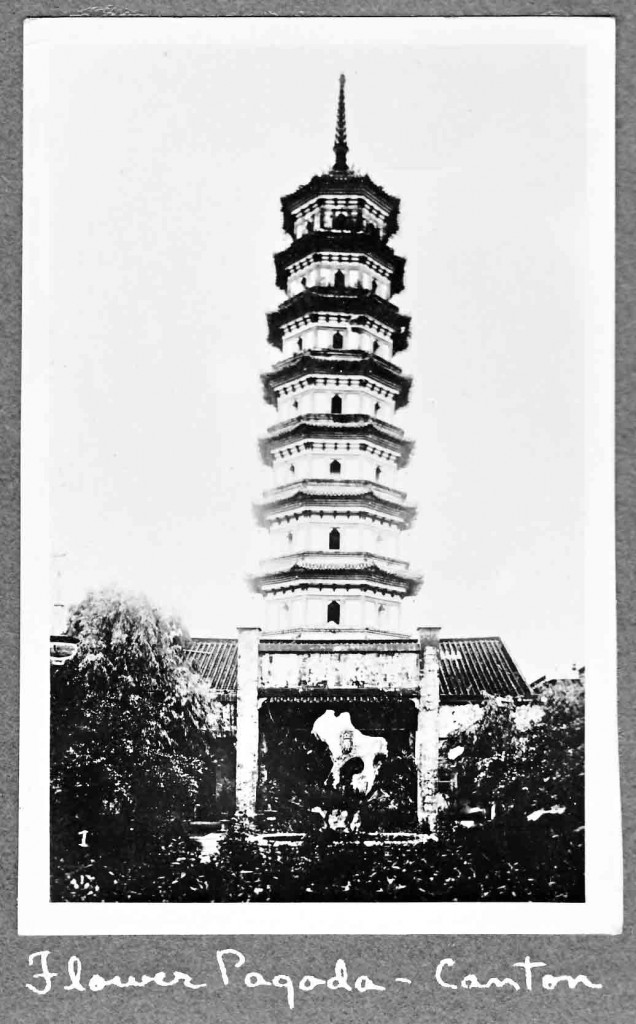

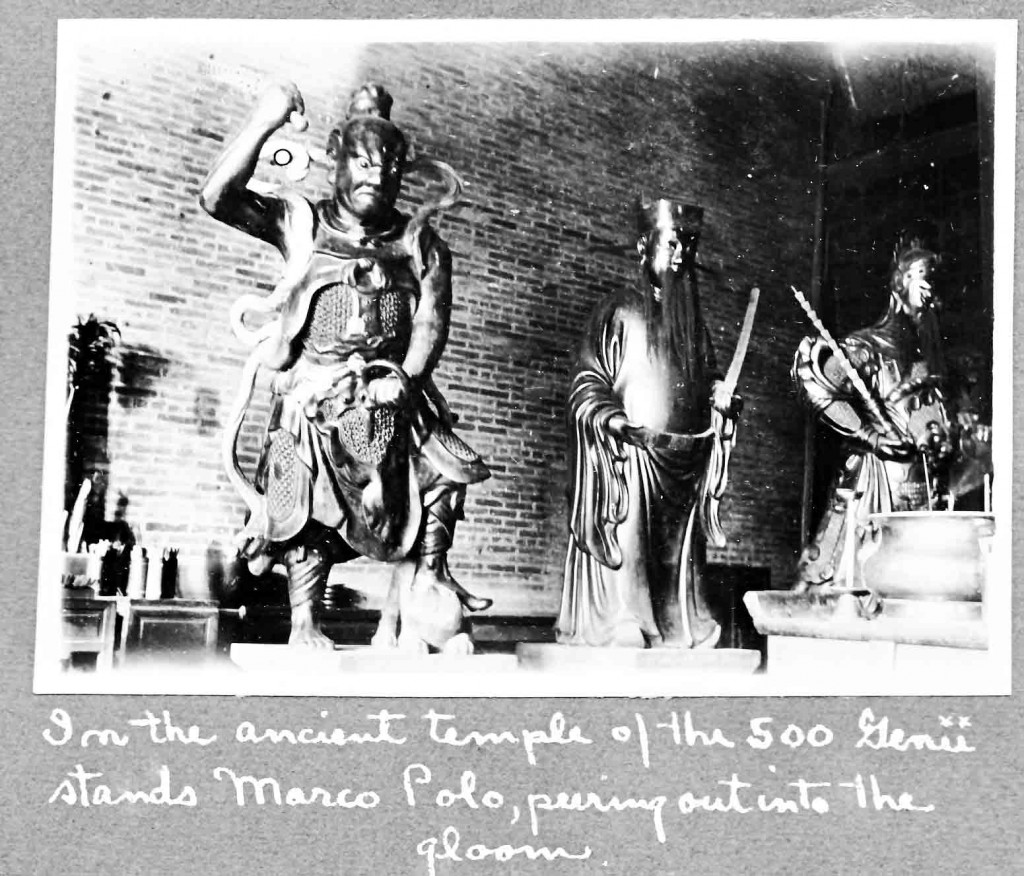

A walk through this district brought us to the nine-storey flower pagoda which is a more or less dilapidated park with a little lake. Not so far away was a temple at the foot of the hill in Canton. Formerly it was a place of beaut,y but now the priests have been replaced by soldiers. The guards would not let us within the walls (everything is walled in China) till two officers came along. Hearing we were Germans, they let us proceed. Had we said we were English, there would have been no getting in.

The temple was entered by a short flight of steps from the level of the second court. Here in the semi-gloom sat the gilded deity behind numerous joss sticks and burning candles. The altar, drapings, building—everything—was much run down. On either side of the door as you entered stood three large demons (gilt) of some sort.

Though it was only in the low eighties in the shade, it was beastly hot. The humidity at Canton is very high and makes it seem much hotter than it really is. Thus when we had gained the top of the hill, we were glad to rest in the shade. A good a view of Canton is had from here—the sea of low roofs—clay tile—the river, etc. The pagoda museum was closed. You can still see remains of the old fort that was once here. Below, at the foot, a large modern museum is being erected.

By taking a motor car, we got back to the college at one—hot and tired. But no rest. Immediately we went to the main dining room of the place where a number of women were gathered to eat together with Dr. Hoffman, the head of the college, and Rev. and Mrs. Dungan from Soochow near Shanghai. I think there were several from Ohio and Rev. Dungan graduated from Ohio State in ’22.

Everybody was jolly as we sat down to a Chinese feed, and slang was running freely. After the soup we attached seven big plates of chow of all descriptions and made of about a little bit of everything under the sun. Beans of several sorts—pieces of bamboo—different kinds of sprouts—mushrooms—fish—eggs—meats, etc. I got along fairly well with the chop sticks and managed to eat about as much as everybody else—which meant second helpings. The dishes are delicious and you don’t realize you are eating so much. The rice requires the most skill to down. It is served in a little bowl and chopsticks and rice doesn’t hang together. So you pick up the bowl, place it to your mouth, and shove in the rice.

I left for Hongkong right after lunch. For once I didn’t get lost and took a rickshaw to the river. The Chinese boats are cheaper, so I boarded what I thought was one and blew myself to second class which gives you a darned nice cabin. Even it is less than a dollar fifty gold for the 6-hour 80-mile river trip. Later I discovered I was on the British boat. Third class was about a dollar and steerage 40¢ gold.

At 4:30 we steamed out into the crowded river and followed the eastern branch from town. I saw the Linan tied up at dock—the boat I take to Shanghai Wednesday.

The country along the river is low, marshy, and a beautiful green. These lowlands extend for miles till they meet the rugged coastal hills. Along the banks the same crowded villages, small craft. To the south the land grew hilly—rolly—and on many of the green summits stood tall pagodas.

As the dusk came upon us, everything had added charm. We passed some huge grass-covered rocks in the river, a good-sized island. As that slipped astern, two native junks crossed our track, outlined against the cloudy pink sky; distant mountains lifted dark peaks low above the horizon on the right, and tall pagodas were gracefully silhouetted against a lighter sky to the left.

Soon darkness closed in. An Indian brought me a cup of tea. He is a sergeant of the police aboard the boat. Sprawling in deck chairs at the stern watching the lights of a following steamer, he told me his yarn—how he had fought near Marseilles during the Great War—how he had been a soldier in the Punjab—finally receiving an old-age pension and came to Hongkong where for the last year he had been on the river.

Soon darkness closed in. An Indian brought me a cup of tea. He is a sergeant of the police aboard the boat. Sprawling in deck chairs at the stern watching the lights of a following steamer, he told me his yarn—how he had fought near Marseilles during the Great War—how he had been a soldier in the Punjab—finally receiving an old-age pension and came to Hongkong where for the last year he had been on the river.

The Pearl River has always been a great traffic lane. In the 17th century the Portuguese were trading here with Hongkong. Then followed the British, and after, the traders of many other nations. Piratery was rife in the early and middle eighteenth century and bandits attacked ships as they sailed up the river past the big rock island. There was constant trouble over the opium trade between China and these foreigners. Several times these latter were maltreated in Canton and their trading places and factories pillaged and damaged. Several times English gunboats and soldiers were forced to wreck the forts and Canton and sink fleets of native war junks. During this strife, the island of Hongkong was ceded to Great Britain by a treaty. At that time it seemed of little value and but little attention was paid to it. The old Portuguese town of Macao also lay near the river’s mouth.

In the end the foreign traders were forced to leave Canton and they settled on Hongkong island where the city of Victoria began to grow rapidly in the latter half of the century. The first years of its existence were hard ones and until the 20th century it struggled on—changing governors every 2 to 5 years as one failed or became broken in health from the strain. Now the population is well over 300,000 I believe. Macao is a gambling center.

Below the rocks the river widens out so you can hardly see land. It was dark now and a cool breeze was a great relief from the heat of Canton. A young Chinaman who worked on the boat came up and talked about an hour. The Indians are placed near the captain—why him I know not. There is still danger from river bandits, though not so much any more. At 10:30 PM we docked at Hongkong and I was soon under a shower at the Y.

Later note: In 1933 bandits boarded a river boat between H.K. and Canton, killing the officers, robbing the passengers, they disappeared into the hills.