Tuesday, June 18, 1929

Big Tamashe!!! Had to visit the Taj again last night. The ride along under the trees shadowing the road is charming enough—but the Taj on a moonlight night—gosh!—just a dream. The moon is nearly full, and sets off the grace and beauty of the white marble in a fancy of romance and love. As one stands on the steps of the Taj Ganj Gate and gazes down the long cypress-lined water vista, sees the Taj stand out as a phantom myth, the inverted image lying still upon the water, the scene seems to typify India—gives one the feeling that all India is summed up in this perfect tribute to womanhood—that this is the symbol of the East.

Being Americans, we had our kodaks with us and took time exposures of the place. Mort climbed a minaret; Frank fell asleep on a bench beside the lily pond, while I watched the cameras and had my daily dozen.

Being Americans, we had our kodaks with us and took time exposures of the place. Mort climbed a minaret; Frank fell asleep on a bench beside the lily pond, while I watched the cameras and had my daily dozen.

At midnight Frank was more asleep than awake. Therefore, Mort and I rolled down through the park, past the fort, and into the bazaars, alone. Parking the bikes we made our way toward a well-lighted section of the bazaar. Here the streets were full of jostling, pushing Moslems, gaily bedecked in many colors, especially the women.

A large ring had been formed in the street, leaving barely enough room on the sides in which to squeeze by. All descriptions of people crowded about, eager to see what was taking place in the center. At one side of the ring a half dozen drummers, some with tom-toms, kept up an incessant din. Behind them stood a cart over which a high framework of thin sticks had been built. These were wrapped with all colored cloths, tinsel, tin-foil of several colors, and from the top hung streamers of tinsel. In the cart were dozens of wooden swords, spears, knives, daggers, and long batons, all richly decorated and colored. Many were real ones of steel. Those in the crowd and along the streets carried these weapons also. One might have thought that there was a revolt taking place.

Within the ring a man and small boy were dueling with two stick-swords (lathis) with blunt points. They parried, twisted this way and that, danced about on one foot and posed a little for the onlookers. In spite of the unequal size of the combatants, the match appeared to be an even one. There was no cheering, but everybody was interested. When the actors were tired, they stopped and others from the crowd stepped up to try their hand at the sport.

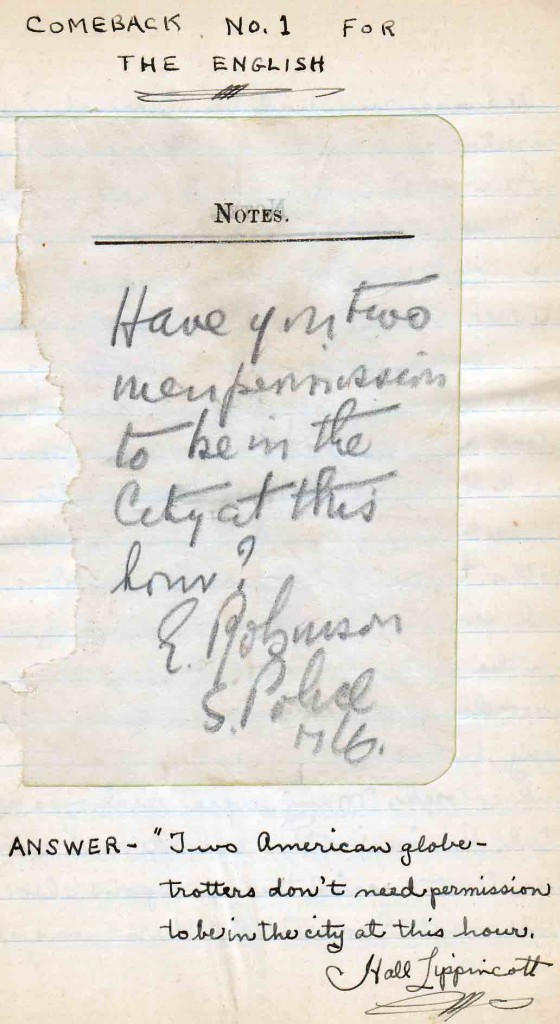

A few feet farther up the street a similar crowd was gathered watching another duel,. On the opposite side of the ring, by the drummers, was a raised platform. Elegance itself was abroad for there sat a half-dozen Englishmen all garbed in white tuxedos. They weren’t particularly interested in the performance before them and immediately spotted me when I climbed upon a wagon wheel to better see the tamashe. A little whispering and a few moments later a policeman brought me the note. After answering it, I located Mort and walked back down the street. Again the British army had had a black eye at our hands for we sure looked like two bums, socks rolled down, collars down and sleeves up—and I had on only one shoe, it being necessary to wear a leather sock on the left foot to fit over the bandage.

While watching another tamashe a block down the street, the cop appeared again and said the gentleman wished to see us. He turned out to be a very decent sort of a chap, very good looking and immaculately dressed as most Englishmen are, especially at middle age. He was some police official, evidently one well up, for he told a general standing at his back to give us any dope [No, not that kind of dope.] we needed. He informed us the celebrations were all in honor or the Prophet’s two sons who were killed in battle—something we had been trying to learn for some days. Said we would get in a row if we pulled a taj. Don’t know what a taj is unless it could be the large temple-like affairs sitting in the shops and carried through the streets. [Does anyone in cyberland know what this meant in 1929?]

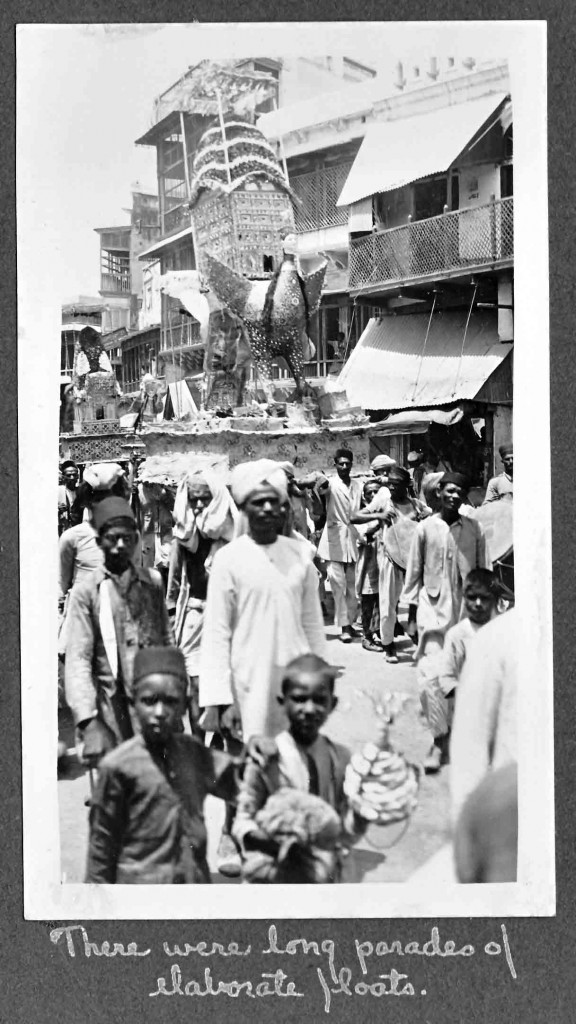

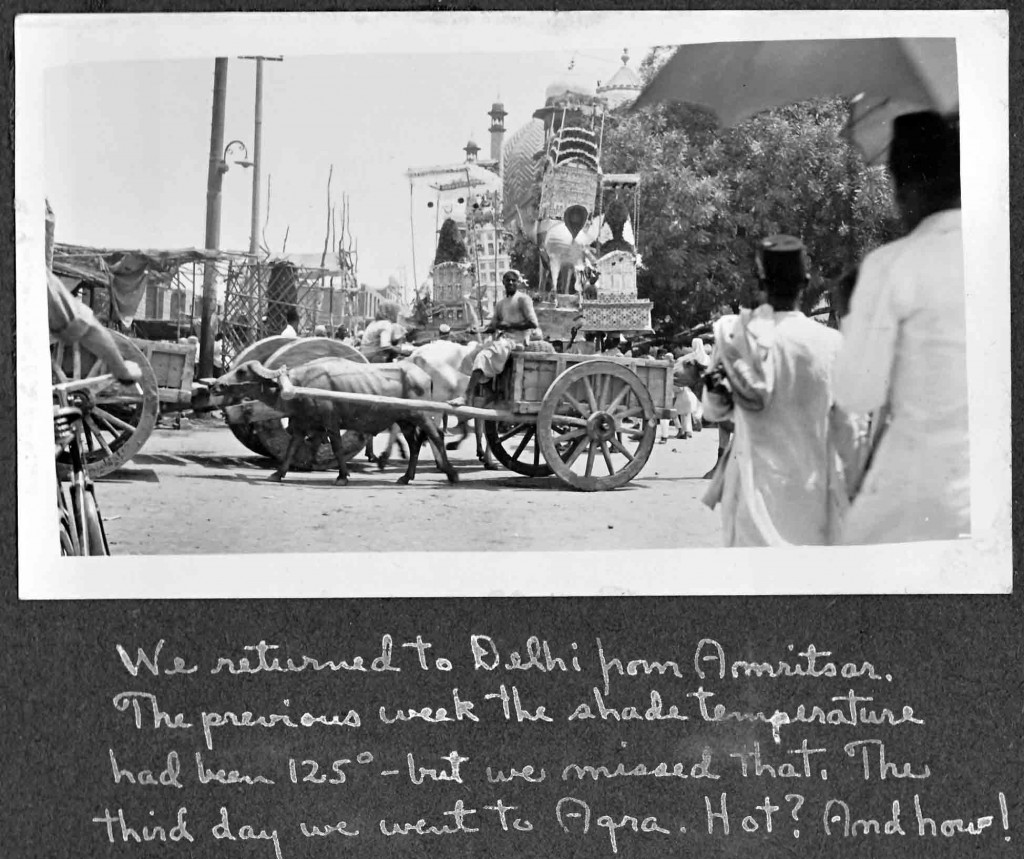

Back at the hotel, we heard another big tamashe in the native section of the cantonment, so rode over to see that. It too was a lively affair—temples 20 feet high borne by eight or ten coolies—banners, swords, lamps, red torches—dozens of tom-toms, the noisy, curious crowd—hundreds of women sitting on the low roofs on both sides of the street, or peeping out from windows.

I am not certain, but believe these ceremonies are continued without cessation throughout the four days. The thing was in progress all day long, and was going strong at one-thirty when we went to bed. It was still on at three when Mort awoke. Wednesday is the last and biggest day. We are very fortunate to be here at this time. Most tourists, in fact but a very few, ever see this—not because it’s hard to see but because of the time of year—the summer when tourists avoid (wisely) the plains of India.

This morning we returned to the bazaars to see more of the tamashe. Parking the bikes, we walked up the main street. It was crowded with people, many carrying the swords, etc. The usual beggars tagged persistently behind, whining for baksheesh. At the scene of last night’s main activities, all was a-bustle. Mobs swayed this way and that, pushing those in front, trying to better see all that was taking place. Many shops had colored paper streamers hanging from the front awning—temples were everywhere, constructed of a light framework of sticks and covered with red, blue, and green paper, with much tinsel and tinfoil sparkling in a dazzling sunlight. These ranged to all sizes. Bloon [balloon] men and those peddling noise-makers wandered through the throng with their gaudy-colored wares. Drums beat unceasingly. As I wandered aimlessly up the drag through this din, I passed stands, colorfully decorated, protruding into the street. Some were Moslem water stands where a man was kept busy dipping water from huge crocks into smaller earthen ones to quench the thirst of sweating mobs. Others contained huge effigies of a horse with the head of a man, of a large man with a very small head—masses of tinfoil and glittering beads mounted upon frail wooden frames. At night these are brilliantly lighted.

This morning we returned to the bazaars to see more of the tamashe. Parking the bikes, we walked up the main street. It was crowded with people, many carrying the swords, etc. The usual beggars tagged persistently behind, whining for baksheesh. At the scene of last night’s main activities, all was a-bustle. Mobs swayed this way and that, pushing those in front, trying to better see all that was taking place. Many shops had colored paper streamers hanging from the front awning—temples were everywhere, constructed of a light framework of sticks and covered with red, blue, and green paper, with much tinsel and tinfoil sparkling in a dazzling sunlight. These ranged to all sizes. Bloon [balloon] men and those peddling noise-makers wandered through the throng with their gaudy-colored wares. Drums beat unceasingly. As I wandered aimlessly up the drag through this din, I passed stands, colorfully decorated, protruding into the street. Some were Moslem water stands where a man was kept busy dipping water from huge crocks into smaller earthen ones to quench the thirst of sweating mobs. Others contained huge effigies of a horse with the head of a man, of a large man with a very small head—masses of tinfoil and glittering beads mounted upon frail wooden frames. At night these are brilliantly lighted.

Wasn’t too long before the three of us were all separated. Lost Mort when he stopped to peer in a shop and last saw Frank on the second-storey balcony of some house taking a snap of a duel in the street below. Goodness only knows how he got there.

I turned down a side street and soon ran into the head of a procession coming slowly up the street. The parade would advance perhaps fifteen or twenty feet, halt for say ten or fifteen, then advance a few more feet. I sat up in a cloth shop to await its coming. A mob immediately collected around me, all pressing forward to see this freakish specimen—one shoe, soaked with sweat, socks down, and trying to get a picture. Such a flattering amount of attention!

They couldn’t do enough for me and were anxious that I was bothered by no one. This interest and courtesy I have found present far more often in the Moslem than in the Hindu—and therefore naturally enjoy being among Moslems much more. Two or three young men with beetle-juice dripping from their mouths offered and insisted upon guiding me down the street. But a guide in that swarm of sweating, sweltering humanity was worse than none. Thousands and thousands squeezed along the narrow, crooked street, under canopies hung from one rooftop to the other. Without this the heat would have been unbearable, for today a merciless sun soared the mercury higher than it has yet been during our stay—probably near 110° or 112° shade. While this conglomeration of people pressed back and forth, sweltering under a mid-day tropical sun, roofs and balconies and windows were also full—but of women and children. But few women were down on the streets. Many above, following the Moslem custom of hiding the women, peeped from behind hangings especially erected on the balcony.

Here the floats were larger and of a greater variety. Most represented what we took to be a temple or tomb, built up rather like a pyramid with the dome on top. Over this was usually a roof or canopy from which streamers of flowers fell. One was constructed of isinglass richly ornamented with tinfoil, imitation red roses, and other glittering objects. Banners made of swords, flags, tom-toms, fifes, drums, noise-makers, plaster dolls and images to represent floats and other features of the “show”—bloons [guess that wasn’t an intentional misspelling after all], beggars, playing children, sweet stands, yelling, the smell of perspiring mobs intermingled with that of savory foods—well, it was some tamashe.

Here the floats were larger and of a greater variety. Most represented what we took to be a temple or tomb, built up rather like a pyramid with the dome on top. Over this was usually a roof or canopy from which streamers of flowers fell. One was constructed of isinglass richly ornamented with tinfoil, imitation red roses, and other glittering objects. Banners made of swords, flags, tom-toms, fifes, drums, noise-makers, plaster dolls and images to represent floats and other features of the “show”—bloons [guess that wasn’t an intentional misspelling after all], beggars, playing children, sweet stands, yelling, the smell of perspiring mobs intermingled with that of savory foods—well, it was some tamashe.

Most of the afternoon was spent inspecting the negatives of our 240 or 250-odd pictures. But 16 of this number were not good—four being due to dropping a film and exposing it to the light. But two, and these four, were really total losses.

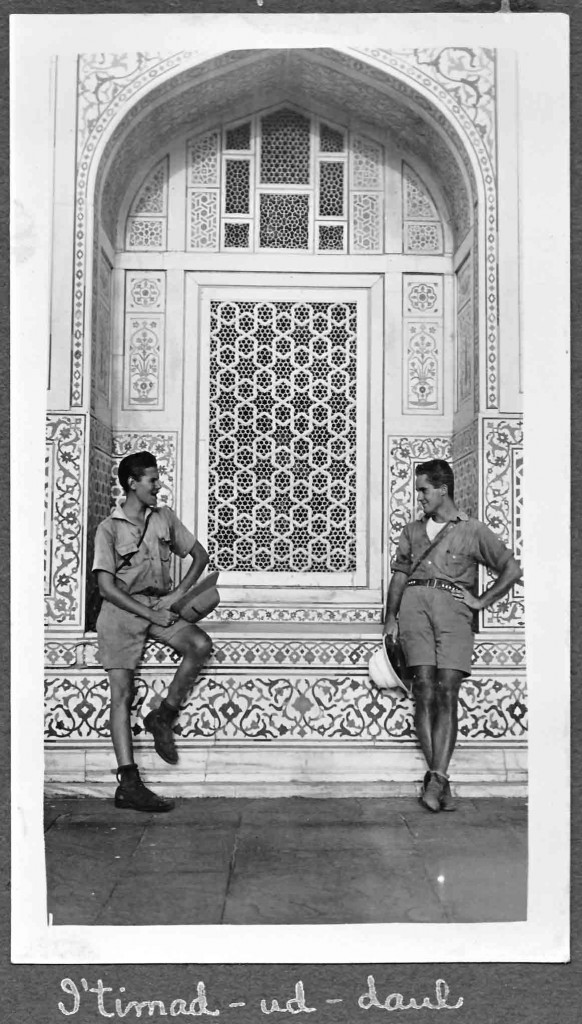

From here we cycled down town, across the Jumna River to the tomb of I’timad-ud-daula. It is a mausoleum of the grandfather of the lady of the Taj. It stands in an attractive garden and is raised on a four-foot platform. It measures 69 feet square itself, and at each corner a tower 40 feet high. Within are several marble tombs. The whole of the exterior and much of the interior is of white marble with beautiful inlay work, the earliest of its particular character known in India. Marble latticed windows are well carved too.

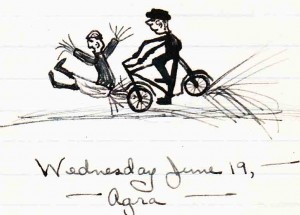

From here we tried to find Akbar’s tomb, but were on the wrong road. We did visit the Rambagh Gardens which must be very nice in winter after the rains. My tires were again acting up, so we returned home a little after dark. En route, Mort succeeded in doing what he had been for all afternoon. After scraping the fenders off a half dozen pedestrians, one finally jumped right in front of him when he rang his bell. Chances are 50 to 1 he rang it a foot from the man. At any rate, the old boy just got picked up and sat down “southward” in the road.

From here we tried to find Akbar’s tomb, but were on the wrong road. We did visit the Rambagh Gardens which must be very nice in winter after the rains. My tires were again acting up, so we returned home a little after dark. En route, Mort succeeded in doing what he had been for all afternoon. After scraping the fenders off a half dozen pedestrians, one finally jumped right in front of him when he rang his bell. Chances are 50 to 1 he rang it a foot from the man. At any rate, the old boy just got picked up and sat down “southward” in the road.