Wednesday, October 30, 1929

“The appearance of Hawaii this morning was exceedingly beautiful. . . .the whole of the eastern and northern parts of the island were distinctly in view, with an atmosphere perfectly clear, and a sky glowing with the freshness and splendor of sunrise. When I first went on deck, the glory of the morning still lingered in the lowlands, imparting to them a grave and sombre shade, while the region behind rising into broader light, presented the precipices and forests in all their boldness and verdure. Over the still loftier heights one broad mantle of purple was thrown, above which the icy cliffs of Mauna Kea blazed like fire, from the strong reflection of the sunbeams, striking them long before they reached us on the waters below.” — Comment of a traveler of 1823. And the scene is not one whit different today. That description fits perfectly what I saw as we steamed down the Hamakua coast at daybreak—all except the snow. That will not be here till next month. Instead I saw the cliffs turn a dull glowing red as if of iron ore—a striking contrast to the dark waters of the sea, dark green of the cane fields, and the blue sky and gray clouds.

The island begins as a mere point of land, and gradually rises to 5,500 ft. From the Hamakua coast it rises from the high sea cliffs very rapidly, knolls and ridges seemingly piled upon one another. The coastline is cut by scores of deep gulches, valleys, and gorges that rise rapidly to meet the hills.

The island begins as a mere point of land, and gradually rises to 5,500 ft. From the Hamakua coast it rises from the high sea cliffs very rapidly, knolls and ridges seemingly piled upon one another. The coastline is cut by scores of deep gulches, valleys, and gorges that rise rapidly to meet the hills.

Then comes a longer slope that lifts the bulk a few thousand feet, and lastly the part that is still in the making (for Mauna Kea is an active volcano), rising another 8,000 feet to the summit, 13,825 ft.

Farther south appears the enormous flattened dome mass of Mauna Loa, but little below its twin volcano, 13,675 ft. The height is baffling, especially that of Mauna Loa which seems so great height. Yet it is 74 by 55 miles at its sea level base. From the plateau of the crater Mokuaweoweo, whose area is nearly 4 square miles, and whose walls are from 500 to 1,000 ft. high, it is more than 30,000 ft. to the floor of the ocean, the world’s largest mountain mass. The land drops off so suddenly that in Hilo Harbor the water is said to be three miles deep in one spot.

Arrived at Hilo at 7:30 AM and I walked it into town, over a mile easily. After breakfast I turned my efforts to a bike hunt and finally had to ask Bell, the Boy Scout executive, to help. With difficulty he located one which I rented for the price of two new tires which I bought and carried all day before putting them on.

The great town of Hilo, 13,000 inhabitants, is not a bad place. It is the country seat of the island of Hawaii and commands a fine view of the twin peaks.

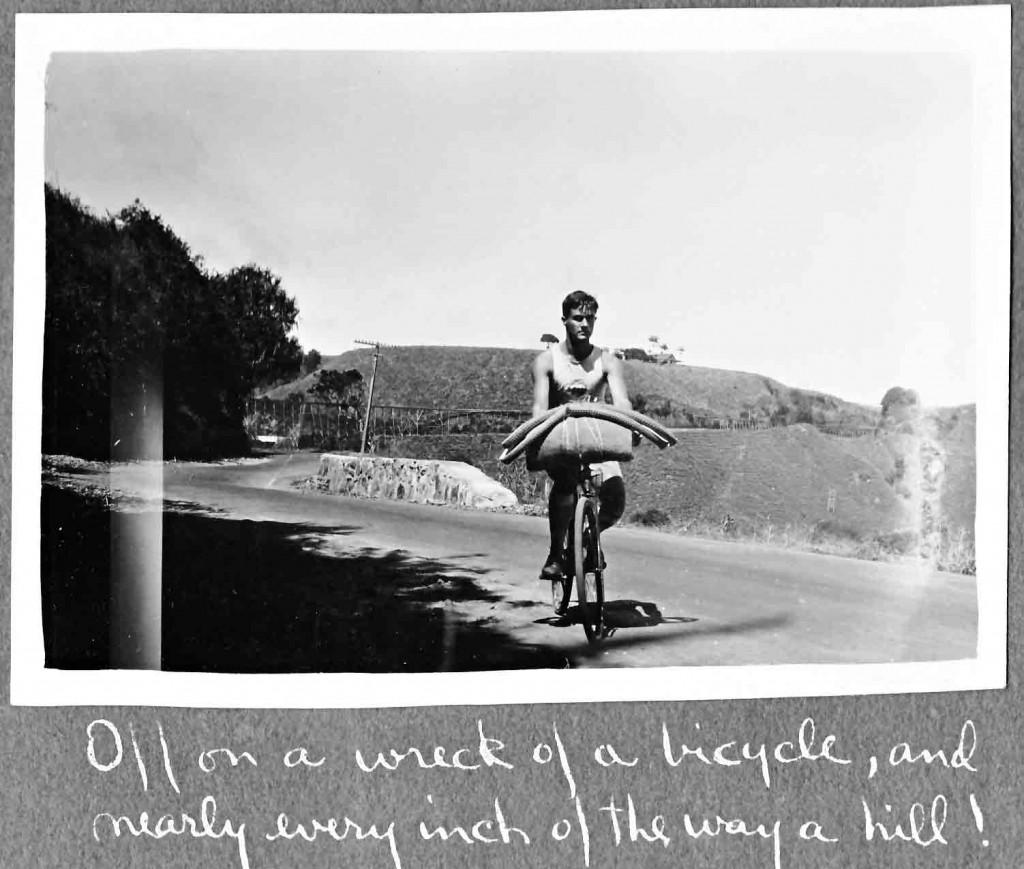

The bike, of ancient vintage, was obviously salvaged from the long-forgotten for my benefit. At any rate it had two wheels and a place to sit, and though it pumped like a ton of bricks, even downhill, it is more or less possible to move forward by the simple process of killing oneself. What can one expect for a dollar a day?

Might as well be optimistic while you can. It’s about 300 miles around the island, and a mighty scenic ride that. I figured I could do it easily in 2½ or 3 days, leaving a day for the volcanoes. My blanket I tied on the handlebars so I could barely glide—and in a mile—hardly pump.

The happy illusions sailed into the mud before I was out of Hilo. The road was perfect all but seven miles of really foul stretch, but it was just one damned hill after another. As I said once before, the coast is cut by scores of gullies, etc. Well, each gully means a coast down and a walk up, for the road turns inland along the hillside, dips down to stream level before crossing, often with an old covered Kentucky wooden bridge, then climbs up again. The railroad runs along the precipices in a more nearly straight line. In its life of 40 miles it crosses over 70 of these ravines, one bridge being 230 ft. high. The road, in the first 48 miles, also climbs about a thousand feet.

The happy illusions sailed into the mud before I was out of Hilo. The road was perfect all but seven miles of really foul stretch, but it was just one damned hill after another. As I said once before, the coast is cut by scores of gullies, etc. Well, each gully means a coast down and a walk up, for the road turns inland along the hillside, dips down to stream level before crossing, often with an old covered Kentucky wooden bridge, then climbs up again. The railroad runs along the precipices in a more nearly straight line. In its life of 40 miles it crosses over 70 of these ravines, one bridge being 230 ft. high. The road, in the first 48 miles, also climbs about a thousand feet.

It is a lovely ride, close by the sea, from 100 to 300 ft. above it. Sugar cane fields meet the eye in every direction—miles and miles of it, 8 and 9 feet high, all snarled and twisted along the ground. It rolls out from you in great green waves down the steep hillside toward the sea. Sometimes you see a hill of it being burned to get rid of the leaves before cutting and hauling to one of the many factories along the coast. Companies have great plantations and small villages of workers, with nice cooperative stores, schools, and recreation grounds. Workers are paid about a dollar a day and given a house to live in and at the present a ten percent bonus. Not so good. During the war the wages were about the same but the bonus was 200%.

A great variety of tropical foliage—plants, ferns, and trees—are to be found in every gorge. Banana trees are common. There are numerous small waterfalls in the streams that come tumbling down their rocky beds to the sea. Everywhere one sees the irrigation troughs for the cane fields, overhead, through fields, across valleys.

But roses don’t bloom for cyclists on that road, and with that bike. What the torrid sun didn’t do wasn’t worth mentioning. Dried my throat miserably, made me sweat like a trooper, sapped all energy from me till I could hardly drag on. One tire had a habit of going flat, and thus when I did come to a hill steep enough to coast down, I wore myself out clamping down on the brakes so as not to crack the rim by going too fast.

At dark I reached Honokaa, 48 miles north of Hilo, eight hours. There I had the new tires put on and ate till I could hardly walk. Spent the night in a grassy plot by a filling station two miles from town. Very pretty night, pleasantly cool, spoiled only by a solo debate as to my plans for the morrow.